Spelling or spelling n (ancient Greek ὀρθογραφία, from ὀρθός - “correct” and γράφω - “I am writing”) - the uniformity of the transmission of words and grammatical forms of speech in writing. Also a set of rules that ensures this uniformity, and the branch of applied linguistics that deals with it.

Spelling or spelling n (ancient Greek ὀρθογραφία, from ὀρθός - “correct” and γράφω - “I am writing”) - the uniformity of the transmission of words and grammatical forms of speech in writing. Also a set of rules that ensures this uniformity, and the branch of applied linguistics that deals with it.

History of spelling in Russia n Initially, individual spellings dominated the language. One of the earliest works on the theory of spelling is the work of V.K. Trediakovsky, published in 1748, where the principles of constructing the alphabet and spelling are formulated, to which even the modern Russian alphabet corresponds well.

History of spelling in Russia n Initially, individual spellings dominated the language. One of the earliest works on the theory of spelling is the work of V.K. Trediakovsky, published in 1748, where the principles of constructing the alphabet and spelling are formulated, to which even the modern Russian alphabet corresponds well.

n M.V. Lomonosov in “Russian Grammar”, published in 1755, which was widely used and was used for many years to teach the Russian language, published spelling rules and such fundamental principles as ease of reading for everyone, proximity to the three main Russian dialects , proximity to morphology and pronunciation.

n M.V. Lomonosov in “Russian Grammar”, published in 1755, which was widely used and was used for many years to teach the Russian language, published spelling rules and such fundamental principles as ease of reading for everyone, proximity to the three main Russian dialects , proximity to morphology and pronunciation.

n A fairly complete review of spelling rules in their historical perspective was carried out by J. K. Grot in 1873. He considered the main principle to be morphological in combination, to some extent, with phonetic written forms. Subsequently, the primacy of the morphological principle (as opposed to phonetic) in Russian spelling was pointed out by A. N. Gvozdev, A. I. Thomson, M. N. Peterson, D. N. Ushakov

n A fairly complete review of spelling rules in their historical perspective was carried out by J. K. Grot in 1873. He considered the main principle to be morphological in combination, to some extent, with phonetic written forms. Subsequently, the primacy of the morphological principle (as opposed to phonetic) in Russian spelling was pointed out by A. N. Gvozdev, A. I. Thomson, M. N. Peterson, D. N. Ushakov

Russian pre-reform orthography (pre-revolutionary) n n The beginning of Russian pre-reform orthography can be considered the introduction of a civil font under Peter I. There was no single generally accepted standard of pre-reform orthography (similar to the Soviet code of 1956). The most authoritative (although not fully observed in the press published at that time) manuals and sets of rules on Russian pre-reform orthography are associated with the name of academician Yakov Karlovich Grot. They relate specifically to the last stable 50th anniversary of the existence of pre-reform spelling.

Russian pre-reform orthography (pre-revolutionary) n n The beginning of Russian pre-reform orthography can be considered the introduction of a civil font under Peter I. There was no single generally accepted standard of pre-reform orthography (similar to the Soviet code of 1956). The most authoritative (although not fully observed in the press published at that time) manuals and sets of rules on Russian pre-reform orthography are associated with the name of academician Yakov Karlovich Grot. They relate specifically to the last stable 50th anniversary of the existence of pre-reform spelling.

Changes in spelling in the twentieth century n n n n 1918 - along with “ъ” they began to use an apostrophe (’). In practice, the use of the apostrophe was widespread. 1932-1933 - periods at the end of headings were canceled. 1934 (possibly earlier) - the use of a hyphen in the conjunction “that is” was abolished. 1935 - periods in capital letter abbreviations were abolished. 1938 - the use of the apostrophe was abolished (in central newspapers it was used at least until May 1945) 1942 - the mandatory use of the letter “ё” was introduced. 1956 - the use of the letter “е” (already according to the new rules) became optional, to clarify the correct pronunciation (“bucket”).

Changes in spelling in the twentieth century n n n n 1918 - along with “ъ” they began to use an apostrophe (’). In practice, the use of the apostrophe was widespread. 1932-1933 - periods at the end of headings were canceled. 1934 (possibly earlier) - the use of a hyphen in the conjunction “that is” was abolished. 1935 - periods in capital letter abbreviations were abolished. 1938 - the use of the apostrophe was abolished (in central newspapers it was used at least until May 1945) 1942 - the mandatory use of the letter “ё” was introduced. 1956 - the use of the letter “е” (already according to the new rules) became optional, to clarify the correct pronunciation (“bucket”).

n n The current rules of Russian spelling and punctuation are the rules approved in 1956 by the USSR Academy of Sciences, the USSR Ministry of Higher Education and the RSFSR Ministry of Education. The regulator of the norms of the modern Russian literary language is the Institute of Russian Language named after V. V. Vinogradov. The refined and supplemented rules developed by the Spelling Commission of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2006 have not yet been approved as of October 12, 2009.

n n The current rules of Russian spelling and punctuation are the rules approved in 1956 by the USSR Academy of Sciences, the USSR Ministry of Higher Education and the RSFSR Ministry of Education. The regulator of the norms of the modern Russian literary language is the Institute of Russian Language named after V. V. Vinogradov. The refined and supplemented rules developed by the Spelling Commission of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2006 have not yet been approved as of October 12, 2009.

Differences between pre-revolutionary spelling and modern spelling n n Before the revolution, the Russian alphabet had 35, not 33 letters, as it is now. The names of the letters of the Russian pre-reform alphabet (modern spelling): az, beeches, lead, verb, good, eat, live, earth, etc., and decimal, how, people, think, ours, he, peace, rtsy, word, firmly, uk, fert, dick, tsy, worm, sha, sha, er, er, yat, e, yu, I, fita, and zhitsa. Aa Zz O B b I and P o Xx b p C c Ѣ ѣ Vv Gg II Kk D d L Ee M l F f N m Rr Ss Tt Uu n F f Chch Sh Shch y w sh y Ee Yu I f Ѵ yu i ѳ ѵ

Differences between pre-revolutionary spelling and modern spelling n n Before the revolution, the Russian alphabet had 35, not 33 letters, as it is now. The names of the letters of the Russian pre-reform alphabet (modern spelling): az, beeches, lead, verb, good, eat, live, earth, etc., and decimal, how, people, think, ours, he, peace, rtsy, word, firmly, uk, fert, dick, tsy, worm, sha, sha, er, er, yat, e, yu, I, fita, and zhitsa. Aa Zz O B b I and P o Xx b p C c Ѣ ѣ Vv Gg II Kk D d L Ee M l F f N m Rr Ss Tt Uu n F f Chch Sh Shch y w sh y Ee Yu I f Ѵ yu i ѳ ѵ

Pronunciation of abolished letters n n n The letter “i” was read as [i] The letter “ѣ” was read as [e] The letter “ѳ” was read as [f] The letter “ѵ” was read as [i] The letter “ъ” at the end of words was not read

Pronunciation of abolished letters n n n The letter “i” was read as [i] The letter “ѣ” was read as [e] The letter “ѳ” was read as [f] The letter “ѵ” was read as [i] The letter “ъ” at the end of words was not read

n n Until 1942, the letter e was absent from the alphabet. The letter y is inscribed in the 1934 alphabet, but the word yod is printed with an i (“iod”). In Ushakov's dictionary, all words starting with th are redirected to analogues starting with i: iog [eg], yoga [yoga], iod [ed], iodism, iodide, iodine, Yorkshire, iota, iotation, iotated and iotated. But in the words ion, ionization, ionize, ionnian, ionnic, ionic, Jordan (b) and and about are read separately. Aa Bb Vv Gy Dd Eh Zz Ii Yy Kk Ll Mm Nn Oo Pp Rr Ss Tt Uu Ff Xx Ts Chch Shsh Shch Ъъ ыы ьь Eee Yuyu Yaya

n n Until 1942, the letter e was absent from the alphabet. The letter y is inscribed in the 1934 alphabet, but the word yod is printed with an i (“iod”). In Ushakov's dictionary, all words starting with th are redirected to analogues starting with i: iog [eg], yoga [yoga], iod [ed], iodism, iodide, iodine, Yorkshire, iota, iotation, iotated and iotated. But in the words ion, ionization, ionize, ionnian, ionnic, ionic, Jordan (b) and and about are read separately. Aa Bb Vv Gy Dd Eh Zz Ii Yy Kk Ll Mm Nn Oo Pp Rr Ss Tt Uu Ff Xx Ts Chch Shsh Shch Ъъ ыы ьь Eee Yuyu Yaya

The ability to create texts and work with them according to the rules of the old spelling n n There are sites that allow you to type text in the old spelling, print it and save it. There are several computer fonts that support the old spelling

The ability to create texts and work with them according to the rules of the old spelling n n There are sites that allow you to type text in the old spelling, print it and save it. There are several computer fonts that support the old spelling

Criticism of Russian spelling n n The spelling of the Russian language has been repeatedly criticized by various writers and scientists. A number of opinions were collected by J. K. Grot in the book “Controversial Issues of Russian Spelling from Peter the Great to the Present” (1873). Y. K. Grot himself defended the letter yat, considering it important for distinguishing words, despite the fact that in the capital's dialects of the oral Russian language such words were not distinguished. The changes to the writing norm that were proposed in this book were very moderate, not affecting frequently used cases with already established spellings. However, for relatively rare words (for example, “ham”, “wedding”, “cuttlefish”), a violation of the morphological nature of their spelling was noted (instead of “vyadchina”, “svatba”, “korokatitsa”). V.V. Lopatin suggested writing in words like loaded, dyed, fried, shorn, wounded always one n, regardless of whether they have syntactically subordinate words or not

Criticism of Russian spelling n n The spelling of the Russian language has been repeatedly criticized by various writers and scientists. A number of opinions were collected by J. K. Grot in the book “Controversial Issues of Russian Spelling from Peter the Great to the Present” (1873). Y. K. Grot himself defended the letter yat, considering it important for distinguishing words, despite the fact that in the capital's dialects of the oral Russian language such words were not distinguished. The changes to the writing norm that were proposed in this book were very moderate, not affecting frequently used cases with already established spellings. However, for relatively rare words (for example, “ham”, “wedding”, “cuttlefish”), a violation of the morphological nature of their spelling was noted (instead of “vyadchina”, “svatba”, “korokatitsa”). V.V. Lopatin suggested writing in words like loaded, dyed, fried, shorn, wounded always one n, regardless of whether they have syntactically subordinate words or not

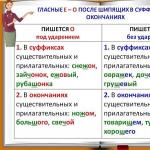

Difficulties of modern Russian orthography n n Integrated or separate spelling of nouns with a prefix that turn into adverbs is determined by the possibility/impossibility of breaking a word into two significant lexical units (to the full, but to death; in half, but in thirds; in addition, but in conclusion, dry, but in sea). The writing o or е after sibilants and ц is inconsistent: arson (noun) with arson (verb), pot with potter. The rule of writing “not” with verbs has many exceptions, also associated with the impossibility of lexical separation of the (first or only) prefix from the root of the word: nayti, hate, unkind, disliked, not received enough, etc. Writing forms of the word “go” (root -i- ) is defined only by the dictionary: to go, but to come and I will come. The same with the forms of the root -im-/ -eat-/-ya-: I will understand, but I will accept, take and take out.

Difficulties of modern Russian orthography n n Integrated or separate spelling of nouns with a prefix that turn into adverbs is determined by the possibility/impossibility of breaking a word into two significant lexical units (to the full, but to death; in half, but in thirds; in addition, but in conclusion, dry, but in sea). The writing o or е after sibilants and ц is inconsistent: arson (noun) with arson (verb), pot with potter. The rule of writing “not” with verbs has many exceptions, also associated with the impossibility of lexical separation of the (first or only) prefix from the root of the word: nayti, hate, unkind, disliked, not received enough, etc. Writing forms of the word “go” (root -i- ) is defined only by the dictionary: to go, but to come and I will come. The same with the forms of the root -im-/ -eat-/-ya-: I will understand, but I will accept, take and take out.

HISTORY OF RUSSIAN GRAPHICS. Modern Russian graphics include an alphabet invented for Slavic writing and carefully developed for the Old Church Slavonic language, which about a thousand years ago was the literary language of all Slavic peoples.

Modern Russian graphics represent slightly modified graphics of the Old Church Slavonic language, the so-called Cyrillic alphabet.

Old Slavonic graphics were compiled in the 9th century. in Bulgaria by the brothers Cyril (Constantine) and Methodius, Byzantine missionaries, scientists and diplomats, on the basis of the Greek alphabet and through the partial use of other alphabets, in particular Hebrew.

From the 10th century Old Church Slavonic graphics began to be used in Rus' when rewriting existing books and when creating original works of writing. The theory of writing and spelling rules did not exist at that time. Scribes who practically mastered the art of writing were mostly copiers of finished manuscripts. This does not mean that Old Russian scribes mechanically used the techniques of the Old Church Slavonic language. While preserving the techniques of Old Church Slavonic graphics in Russian writing (in particular, the letters of nasal vowel sounds that did not exist in the Russian language), Russian scribes adapted it to Russian pronunciation.

In the XII-XIII centuries. Russian writing is increasingly freed from Old Slavonic influence and is gradually turning into an independent system that brings writing closer to living speech.

Due to the historical development of the language, the strengthening traditions of Russian writing, naturally, should have been in some contradiction with the natural changes in the phonetic and grammatical system of the language. This is how a certain discrepancy arose between the graphic and sound systems of the Russian language, between the emerging tradition of writing and pronunciation.

The scribes' reliance on pronunciation led to certain changes in the writing schedule. By the 13th century. the letters ъ and ь, which in the Old Russian language denoted special vowel sounds in certain phonetic conditions, are replaced under stress, in accordance with the new pronunciation, by the letters o, e. Since the 16th century. the letter ь generally loses its sound meaning and becomes a sign of soft consonants and a dividing sign, and the letter ъ is used to designate hard final consonants. On the other hand, the established tradition of writing (reliance on pronunciation) was not particularly effective in the designation of consonants, voiced-voiceless pairs, as well as in relation to akanya (the pronunciation of unstressed o as a). Voicing and devoicing of consonants and acane, which appeared in the phonetic system of the language, were not widely reflected in writing. Pronunciation and tradition - these contradictory factors of writing - turned out to be progressive and equally effective in the development of Russian graphics and spelling.

Of great importance in the history of Russian graphics and spelling was the decree on the introduction of the Russian civil alphabet, issued in 1708 by Peter I. This event, which was an indicator of the decline in the authority and influence of the church, was expressed in some changes in the appearance and composition of the Russian alphabet: unnecessary for Russian sound system of letters, “title” (abbreviations) and “sily” (emphasis) are eliminated. The strengthening of graphics and spelling was also facilitated by the opening in 1727 of an academic printing house, the publications of which adhered to a certain spelling system.

Over the thousand-year period of its existence, Russian graphics have undergone only partial improvements, while the sound system of the living Russian language has continuously, although not always noticeably, changed. As a result, the relationship between Russian graphics and the sound system of the Russian language in our time has turned out to be devoid of complete correspondence: not all sounds pronounced in different phonetic positions are indicated in writing by special letters.

The modern Russian alphabet has 33 letters.

HISTORY OF RUSSIAN SPELLING. Printing, which arose in Russia in the 16th century, played a positive role in the establishment of a uniform letter. Printed materials become a model for all writers. Until the 16th century Russian scribes wrote one word after another without spaces between them. Separate spelling of words is associated with the development of printing.

At the turn of the first half of the 18th century. Issues of graphics and spelling are being posed in principle. They are associated with issues of the Russian literary language and acquire social significance.

The first to raise the question of the basis of Russian orthography was Trediakovsky. In his treatise “A conversation between a foreigner and a Russian about ancient and new spelling and everything that belongs to this matter” (1748), Trediakovsky proclaims the phonetic principle of spelling. Considering that phonetic writing is most accessible to the masses, Trediakovsky, however, recognizes only the correct pronunciation of people who know the norms of the literary language, and makes a number of concessions to traditional spellings. Trediakovsky did not solve the question of the essence of our spelling; his views were not decisive in the history of our spelling.

M.V. Lomonosov included discussions about spelling in his Russian Grammar (1755). Lomonosov's characterization of the theoretical foundations of spelling represents a combination of the phonetic principle of spelling with the morphological one. Paying attention to tradition in writing, Lomonosov covers a wide range of spelling issues related to grammar. Despite their authority and persuasiveness, Lomonosov's rules have not received universal recognition. The rules were not approved by the highest government agency and did not have the force of law. The establishment of spelling standards proposed by Lomonosov was facilitated by the works of V. Svetov and A.A. Barsov, authors of school-type grammatical works. In their works, these authors gave a brief set of spelling rules of the second half of the 18th century, implementing the morphological principle of spelling established by Lomonosov. The final approval of the morphological principle of spelling is associated with the publication of the “Russian Grammar” by the Academy of Sciences (1802, 1809, 1819) and the “Dictionary of the Russian Academy” (1789-1794). The spelling standards established in the mid-18th century were not stable. Significant differences in spelling were noted both in official documents and in the works of writers.

Grammars compiled at the beginning and middle of the 19th century. (Vostokov, Grech, Davydov, Buslaev), and the dictionaries published at that time could not eliminate the spelling discrepancy, which continued throughout the 19th century.

N.A. contributed a lot of useful things to Russian orthography. Karamzin, who influenced spelling practice with his authority (substantiation of the spelling of Russian and foreign words, introduction of the letter ё instead of io).

An extremely important milestone in the history of Russian orthography is the major work of Academician Y.K. Grota “Controversial Issues of Russian Spelling from Peter the Great to the Present” (1873, 1876, 1885) and his book “Russian Spelling” (1885), which is a practical guide for school and print. Grot's work is dedicated to the history and theory of Russian spelling. It covers practical issues of spelling from a scientific perspective. The set of spelling rules compiled by Grot played an important role in establishing spelling standards. The spelling established by Grotto was recommended and received the reputation of being academic, but it did not completely destroy the inconsistency, and most importantly, it did not simplify Russian spelling. Grot jealously adhered to the principle of legitimizing tradition and ignored the movement to simplify writing, which gained wide public momentum in the 50s and 60s of the 19th century. Therefore, Groth’s “Russian Spelling” did not meet with unanimous and complete recognition.

At the beginning of the 20th century. Increasingly broader social tasks of spelling reform are being identified, and the leadership in solving spelling issues is provided by the Academy of Sciences. The resolution on spelling reform, adopted at a broad meeting at the Academy of Sciences on May 11, 1917, had no practical significance. The reformed spelling remained optional for school and printing. Only the Soviet government, by decrees of December 23, 1917 and October 10, 1918, approved the resolution of the meeting of the Academy of Sciences. The new spelling was declared mandatory for all Soviet citizens.

Spelling reform 1917-1918 significantly simplified and facilitated our writing, but did not touch upon many particular issues of spelling, which served as a source of inconsistency in writing practice. This undermined the general spelling system and caused many difficulties in the work of publishing houses, as well as in school teaching.

In 1930 an organized attempt was made to bring about a radical reform of our writing. The draft of such a reform was drawn up by a special commission of the People's Commissariat for Education. The project introduced a disruption in Russian spelling that was not caused by a genuine need in life, moreover, it was not scientifically justifiable, and therefore practically impractical. The project was rejected. The need to streamline spelling became increasingly urgent.

“The task of the present moment is not to reform writing methods, but to streamline some of them towards uniformity and consistency and to resolve individual puzzling cases... Having established everything that has not been sufficiently established so far, it is necessary to publish a complete spelling reference book, authorized by the educational authorities,” - This is how prof. determined the further path of development of Russian orthography. D.N. Ushakov.

The implementation of this task began in the mid-30s, when work was organized to compile a complete set of spelling and punctuation rules. The result of the long work of philologists and teachers was the “Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation”, approved in 1956 by the USSR Academy of Sciences, the USSR Ministry of Higher Education and the RSFSR Ministry of Education. The rules are mandatory for all users of writing, both for press organs, educational institutions, state and public organizations, and for individual citizens.

“Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation” is, in essence, the first complete set of rules of modern Russian spelling in the history of Russian writing and consists of two parts - spelling and punctuation - with the appendix of a dictionary of the most difficult or dubious spellings. A spelling dictionary (110 thousand words), compiled on the basis of the “Rules,” was published in 1956. The “Rules” formed the basis for a number of reference books, dictionaries, and manuals (see § 46).

However, by the end of the 20th century. The 1956 “Rules” are largely outdated and do not currently reflect emerging trends in spelling. Therefore, a special commission has been created at the Institute of Russian Language of the Russian Academy of Sciences, whose task is to create a new set of rules for spelling and punctuation.

Periodic adjustment of the rules is natural and quite natural, since it meets the needs of the developing language and the practice of covering it.

RUSSIAN SPELLING REFORM: PROPOSALS,

–– Write consistently without the letter th before e common nouns with the component -er; accept the changed spellings conveyor, stayer, falsefire, fireworks; approve the spelling of player for the new word (eliminating hesitation). In other words (mostly rare and exotic), keep the spelling of the letter th before e, yu, ya: vilayet, doyen, foye; Kikuyu; hallelujah, vaya, guava, maya, papaya, paranoia, sequoia, tupaya, etc.

–– Write the words brochure and parachute (and their derivatives) with the letter y (instead of y), since they are consistently pronounced with a hard sh. This brings under the general rule the writing of two common words from among the exceptions that did not obey the rule about writing the letter y after sibilants. Spellings with the letter yu after zh and sh are preserved in the common nouns julienne, jury, monteju, embouchure, pshut, fichu, schutte, shutskor, in which soft pronunciation zh and sh is not excluded.

–– extend the spelling with ъ to all complex words without connecting vowels; write with ъ not only words with the first components of two-, three-, four- and the words pan-European, courier (spellings provided for by the current rules), but also write: art fair (a new word with the first part art- in the meaning of “artistic”, cf. art show, art market, etc.), hyperkernel (where hyper is not a prefix, but part of the word hyperon), Hitler Youth.

–– Write the adjective windy with two n (instead of one) - as all other denominate adjectives are written with this suffix, always unstressed: cf. letter, painful, watch, maneuverable, meaningless, etc., including other formations from the word wind: windless, windward, leeward (but: chicken pox, chickenpox - with a different suffix). Also write words derived from windy: windiness, windy, anemone, windy (predicative: it’s windy outside today).

–– Write together formations with the prefix ex- in the meaning of “former”, which is connected with nouns and adjectives, for example: ex-president, ex-minister, ex-champion, ex-Soviet - the same as formations with the same prefix in the meaning of “outside”: extraterritorial, expatriation. The combination in the code of 1956 (§ 79, paragraph 13) of the more freely functioning component ex- with the hyphenated components chief-, non-commissioned, life-, staff-, vice-, found in a narrow circle of job titles and ranks, does not has compelling reasons.

–– Write compounds with the component pol- (“half”) always with a hyphen: not only half a leaf, half an orange, half eleven, half Moscow, but also half a house, half a room, half a meter, half -twelfth, half past one, etc. The unification of spellings with pol- replaces the previous rule, according to which spellings with pol- before consonants were distinguished, except for l (fused) and spellings with pol- before vowels, consonant l and before a capital letter ( hyphens).

–– Eliminate exceptions to the rule of continuous spelling of complex nouns with connecting vowels, extending continuous spelling to: a) names of units of measurement, for example: bed, parking place, passenger kilometer, flight sortie, man-day; b) the names of political parties and trends and their supporters, for example: anarchosyndicalism, anarchosyndicalist, monarchofascism, monarchofascist, left radical, communopatriot. In the set of rules of 1956 (§ 79, paragraphs 2 and 3), such names were proposed to be written with a hyphen.

–– Write with a hyphen the pronoun each other, which is actually a single word, although it is still written separately. It belongs to the class of pronoun-nouns and constitutes a special category of them - a reciprocal pronoun (see, for example, the encyclopedia "Russian Language", 1997, articles "Pronoun" and "Reflexive Pronouns").

–– Replace the separate spelling of the following adverbs with a continuous one: in the hearts, dozarez, doupad, noon, midnight, canopy, groping, afloat, galloping, nasnosyah, stand up, and also not averse. The process of codification of fused adverbs is traditionally of a purely individual nature, i.e., it is aimed at specific linguistic units. The selective approach to consolidating the continuous spellings of adverbs is due, on the one hand, to the stability of writing traditions, and on the other, to the living nature of the process of separating adverbs from the paradigm of nouns and the resulting possibility of different linguistic interpretations of the same fact.

Moscow Department of Education

State educational institution

Higher professional education in Moscow

"Moscow City Pedagogical University"

University of the Foreign languages

Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

Coursework on the topic:

Reforms of Russian spelling

Moscow 2013

Introduction

Over the past decade, the upcoming “spelling reform” has become a favorite topic of public discussion. They often write and speak, confusing language and spelling, about the reform of the Russian language.

Current spelling is a product of long historical development. The rules of Russian spelling were formed gradually, primarily under the pen of classical writers. A significant milestone that marked the systematization of writing rules was the appearance of the works of Academician J. K. Grot “Controversial Issues of Russian Spelling from Peter the Great to the Present” (1873) and “Russian Spelling” (1885; 22nd edition - 1916). They studied according to the “Grotian” rules both before the revolution and (with amendments to the reform of 1918) after it. In 1956, the officially approved “Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation” were published, which still retain their legal force. They played an important role, since they regulated many of the patterns of modern Russian spelling. But it has long become clear that these rules are outdated. Almost half a century has passed, during which time the language itself has developed, many new words and constructions have appeared in it, and the practice of writing in some cases began to contradict the formulated rules. It is not surprising that the text of the 1956 rules itself is now few people know, they have not been used for a long time, and in fact they have not been republished for about thirty years. They have been replaced by various reference books on Russian spelling for press workers and methodological developments for teachers, and in these publications one can often find (as teachers, editors, and proofreaders themselves note) contradictions.

In these conditions, preparing a new, modern text of Russian spelling rules is a long overdue task. A draft of such a text was prepared at the Russian Language Institute. V. V. Vinogradov Russian Academy of Sciences. Having barely appeared in print in 2000, the project caused a mixed reaction from experts and the public, so its implementation was postponed indefinitely. In this regard, the issue of reforming the rules of Russian spelling still remains one of the most pressing. This determines the choice of the topic of our research. The purpose of our work: to consider projects for reforms of Russian spelling. To achieve the goal, we need to solve the following tasks:

Provide a brief overview of the reforms of Russian orthography from the time of Peter the Great to the 1964 project.

Consider the main provisions of the Russian spelling reform of 2000.

The work has a traditional structure and consists of an introduction, two chapters and a conclusion. A list of sources used is provided at the end.

Chapter 1. Spelling

The concept of spelling ORTHOGRAPHY - a) a historically established spelling system that is accepted and used by society;

b) rules ensuring uniformity in cases where variations are possible;

c) compliance with these rules;

d) part of the science of language. The basic unit of spelling is SPELLING. A spelling is a grapheme (letter), whose spelling is potentially variable and therefore must be determined by the application of a special spelling rule. But the concept of an orthogram is broader than a grapheme, since not only the spelling of a letter can be variable in written speech, but also, for example, the space between words, as well as special characters - hyphen, accent, apostrophe, other diacritics (in other Greek ., for example, an aspiration sign). Moreover, if a letter can be variable, then the spelling should not have any variability, but only obligateness, otherwise the meaning of spelling is lost. The basic unit of spelling is the ORPHOGRAM. This is a spelling that follows rules or tradition and is chosen from a number of possible ones. This can be not only a letter, but a hyphen, space, hyphen, lowercase or uppercase. The spelling is not contained in every word, not in every space, but only where spelling variations are possible. So the word STILL can be written in 48 ways. The importance of spelling regulation can already be seen from here. But not every spelling variation is associated with spelling: *FUTURE - violates not the spelling, but the grammatical (morphological) norm; *SUPPORTED instead of SUPPORTED - paronymic violation of the lexical norm; *CONGRATULATIONS - spelling, etc. These are errors not only in written, but also in oral speech (non-literary pronunciation), a violation of the language system, and not the norm. Hence the central concept of spelling - NORM. Of course, it is broader than spelling itself and applies to the entire literary language. NORM is the uniform principles of pronunciation, writing, and phrase construction developed in a language with the participation of exemplary literature, culture and authoritative personalities. The spelling norm is the specificity of written speech and forms a unity with orthoepic, lexical, stylistic, and grammatical norms. Russian spelling as a system of rules is divided into 6 sections:

) rules for transmitting sounds and phonemes by letters as part of words and morphemes;

) rules for continuous, hyphenated and separate spellings;

) rules for lowercase and uppercase letters;

) transfer rules;

) rules for graphic abbreviation of words;

) rules for the transfer of borrowed names of onomastics and toponymy. From the concept of SPELLING, let's move on to the more general concept of SPELLING PRINCIPLE. For example, VODA and WADA are read the same, and both spellings do not affect the correctness of perception. But one of them is spelling incorrect: spelling correctness “doesn’t matter” which one you choose - you just need it to be one, uniform for everyone. As a rule, weak positions of phonemes are conveyed variably in writing. In this case, the choice of spelling is dictated by a certain general idea. Some unified approach. This is what we will call the SPELLING PRINCIPLE - the guiding idea of the choice of letters by a native speaker, where the sound can be indicated variably. Consequently, then the concept of SPELLING can be considered as the result of the application of the principle of spelling.

History of spelling and its principles of construction. There is no point in talking about spelling for the first stage of writing - hieroglyphic or pictographic. After all, with such writing, an idea, a concept is conveyed - we can talk, rather, about calligraphy, an accurate and beautiful drawing. Syllabic writing is already focused on spelling: in Japanese, a certain combination of letters cancels out the vowel, and in Sanskrit too. But the true role of spelling becomes clearer in letter-sound writing, in which ideally each phoneme isolated by consciousness should be represented by a separate letter. But at the same time, options are possible. VADNOY FROM THE ADDED STREETS OF MASCVA... (L.V. Shcherba). It is clear that this is not modern Russian writing. This means that our writing also reflects some conventions that are not directly related to the actual sounding speech flow. Theoretically, three approaches to transmitting audio speech are possible. 2.1. Phonetic principle.

Write as you hear it. This spelling is based on the phonetic principle. Ideally, any language strives for phonetic writing, and all the first types of writing were phonetic - Greek, Latin, Old Church Slavonic. However, as the language develops, the pronunciation changes, and the spelling, as more traditional, lags behind. The contradiction that has arisen must be socially consciously regulated, as if elevating the principles of regulation to the rank of law, legitimizing the relationship between letter and sound, which was previously unambiguous and did not need a law. If the spelling is brought back into relation to the pronunciation, this is a phonetic principle (Serbian language, partly Belarusian language).

1.1 Traditional principle

The opposite case is when the gap is consciously fixed. In English orthography, writing has remained at the level of Chaucer's times (14th century), but pronunciation, on the contrary, is changing extremely quickly. We will call this principle traditional. It is also used in French spelling. Russian spelling of the 19th century also gravitated towards the traditional principle, in particular reflecting Ъ, ь, “yat”, which were not actually pronounced.

1.2 Morphological principle

Modern Russian writing is built on a morphological principle. This is a kind of middle option, since spelling diverges from pronunciation, but only in certain parts - it is predictable and regulated by strict laws. Morphological spelling is based on the desire to understand the structural division of speech into significant segments (morphemes, words). Therefore, its goal is to ensure that these segments are reflected uniformly in writing. This allows you to “grasp” when reading and writing not just the phonetic, but the semantic division of speech, which makes it easier to understand the meaning. Therefore, it would be more accurate to call this principle morphematic. Since the uniformity of morphemic composition is associated, according to the IFS, with a uniform display of the phoneme, regardless of its different phonetic variants, the IFS calls this principle phonemic (phonological). WATER, WATER, VODIANY - uniformly display the morpheme VOD- in writing, although phonetically they sound differently: VAD-, VOD-, VЪD-. Already here the convenience of the morphological principle is visible; otherwise, we would hardly recognize related words - and therefore would not be able to see their systemic connection and structural division. The morphological principle is also used in other Slavic languages - Ukrainian, Czech, Bulgarian, Polish. But in reality, all three principles are present in all orthographies, and their ratios are different in different eras. In Belarusian, too, the phonetic principle is applied only to vowels. And in the sphere of consonants the morphological principle is reflected. Therefore, we can only talk about different degrees of preferential use of one of them compared to the others. The leading principle of Russian orthography is morphological. It is based on the non-indication of positional alternations of vowels and consonants in writing, not only in roots, but also in other morphemes. Thus, for roots we can note the following orthograms, built on a morphological principle: 1) unstressed vowels in the root; 2) dubious consonants at the root; 3) unpronounceable consonants. For prefixes - spelling of vowels and consonants in prefixes, except for prefixes with 3/C and PRE/PRI; double consonants at the junction of prefix and root. For suffixes - vowels and consonants in suffixes of nouns, adjectives and participles - except after sibilants and N/NN; consonants at the end of a word. For endings - vowels in case endings of adjectives and nouns. The morphological principle is a consequence of changes in the sound system of the Russian word; in particular, AKANYE, the fall of the reduced. It is a consequence of the real existence in the mind of the semantic division of speech into morphemes. It is interesting that when the etymology of a word is obscured for us, we tend to write phonetically rather than morphologically - that is, when the semantic structure of the word is not important to us; Wed HERE, WHERE, IF. The loss of direct correlation with the generating word (“de-etymologization”) also leads to a transition from morphological spelling to phonetic (WEDDING - but SVAT; cf. THRESHING - THRESHING). The situation is more difficult with spellings after sibilants. Apparently, Y after Ts and I after Ch or Shch in endings is morphological, but not I after Zh and Sh. The presence of I in suffixes after Zh, Sh, Ch, Shch - type MEDICINE can be recognized as morphological. ЁТ after Ж and Ш in the endings of the verb corresponds to ЁТ of the type BEARS (as in participles ending in ЕНН). Apparently, CHA/SCHA and CHU/SHU, and ZHI/SHI in roots will not be included here, similarly with the spelling O and E in roots after sibilants and Ts. But in the Russian language there are also violations of the morphological principle associated with de-etymologization or other reasons. Theoretically, two types of violations are possible - in favor of phonetic spellings and in favor of traditional spellings.

Chapter 2. Reforms of Russian spelling

Everyone agrees that spelling should be stable, convenient, and consistent. In the case of the Russian language, the problem of improving spelling still remains relevant. And, although during the twentieth century, language policy relating to the Russian language included several “waves” of spelling changes, the problem of not only scientific development, but also the practical comprehensive implementation of spelling innovations was rather little developed theoretically.

The question of spelling in modern societies goes beyond the scope of an applied linguistic or educational problem, since spelling, along with the flag and anthem, is a symbol of state unity. It is not without reason that the most striking spelling reforms are associated with changes in the political system (in the history of Russia these are Peter the Great’s reforms and the reform of 1917, which owed its implementation to two revolutions at once). In modern times, the need to unify writing in education and office work is associated with the general regulation of the activities of social and state institutions. Science (linguistics) plays an expert and legitimizing role in the regulating undertakings of the state (“development of the national language”); Thus, already from the 17th century, special language codification bodies appeared - academies or branches of national academies of sciences, which were responsible for the preparation and publication of dictionaries, grammars, and so on.

In Russia, over the past years (late 1990s - early 2000s), another option for improving Russian spelling has been discussed. It was not implemented, but has not yet been taken off the table: after heated debates in the early 2000s and the subsequent “rollback,” work on the proposals returned to specialists. In the ensuing pause, it became possible to consider various projects not only from a pragmatic plane (although usually retrospective works on this topic appear when the issue of reforms again appears on the agenda). When discussing these innovations, two meanings of the concept “spelling reform” are used. A narrower one, when only significant changes in spelling are called a reform (then only a project adopted in 1917-1918 can be considered a reform in the twentieth century), and a broader one, when a reform is called any proposal to change already adopted spelling norms (in this case, a reform can be name other projects). To an ordinary competent native speaker, anything that changes the usual spellings and rules seems like a reform.

In further discussions about the possibilities and factors of successful spelling reform, the positions of linguists, the mechanisms for developing and accepting spelling changes, the role of the state and social factors, the attitudes of different user groups towards the reform and forecasts of future changes will be consistently considered.

2.1 Pre-reform spelling

Russian pre-reform orthography is the orthography of the Russian language that was in force before its reform in 1918 and was later preserved in emigrant publications. The introduction of the civil script under Peter I can be considered the beginning of Russian pre-reform spelling. There was no single generally accepted standard of pre-reform spelling (similar to the Soviet code of 1956). The spelling of the last approximately 50 years before the 1917 revolution (1870s-1910s) was standardized to a greater extent than the spelling of the first third of the 19th century and especially the 18th century. The most authoritative (although not fully observed in the press published at that time) manuals and sets of rules on Russian pre-reform orthography are associated with the name of academician Yakov Karlovich Grot. They relate specifically to the last stable 50th anniversary of the existence of pre-reform spelling. Before the revolution, the Russian alphabet had 35, not 33 letters, as it is now. It included: and decimal, (er, ery, er) yat, fita, izhitsa, but there were no letters e and y. The most interesting thing is, what is the letter? was not officially abolished; there is no mention of it in the decree on spelling reform. The “writings” ё and й were only formally not included in the alphabet, but were used in exactly the same way as now. “Writing” was called “and s short”. Pronunciation of abolished letters and rules for using abolished letters

The letter i was read as "and".

Letter? read as "e".

The letter fita was read as "f".

The letter Izhitsa was read as “and”

The letter ъ at the end of the words was unreadable.

Thus, for the sound [f] there were two letters - f and fita, for the sound combination [ye] there were also two letters - e and yat, and for the sound [i] - three letters - i, i and?.

The letter i was used before vowels (including e, e, yu, ya) and before й. And also in the word mir with the meaning of the universe, to distinguish it from the word mir - peace, silence. The only exceptions were words like five-arshin, seven-story

Letter? was used in 128 roots of words in the Russian language, as well as in several suffixes and endings.

To make it easier to learn the list of roots with?, poems with? were invented:

B?ly, B?d?, B?d b?s Killed the hungry in the l?s. He beat the hell out of him, drank R?dkoy with the hr?nom, and for the bitterness he gave about the b?d. Give me, brother, what is the cage and the cage, the grid, the grid, the mesh, the water and the iron, - that’s how it should be written. Our eyelids and eyelids Protect the eyes of the eyes, Our eyelids close our eyes, At night, every person... Broke his eyelids, Tied his eyes, St. strong air during prom?n?, for two days? sold hryvnias to V?n?. Dn?pr and Dn?str, as everyone knows, Dv? r?ki in the community? t?at sleep, D?lit the area of their Bug, R?sets from the north to the south. Who's really ferocious there? How dare you speak like that? We need to peacefully argue and kill each other... Bird's nests should be lit up, It's in vain to litter, Laugh at the dirty shit, Laugh at the ugliness. hang out...

The letter fita was used in words that came into Russian (previously in Church Orthodoxy) directly from the Greek language instead of the Greek letter theta. There were few commonly used words with this letter.

Proper names: Aha ?ya, A ?anasiy, A ?ina, Var ?Olomei, Golia ?ъ, Mar ?ah, Mat ?she, Me ?Odiy, Pi ?agor, Iudi ?b, ? eodor...

Geographical names: A ?ins, A ?he, V ?Leem, Ge ?simania, Golgo ?ah, Kar ?agent, Corin ?ъ, Mara ?he, E?i opiya...

Peoples (and city dwellers): Korin ?yane, ski ?s, uh ?i experience... Common nouns: ana ?ema, aka ?ist, apo ?eoz ari ?metics, di ?iramb, op ?ogre ?i me, ri ?ma, eh? ir...

The letter Izhitsa was used in the word mYro to distinguish it from the words mir and mir, and also, according to tradition, in several other words of Greek origin instead of the letter upsilon (like miro, these are mainly words related to the church). By the beginning of the twentieth century, these were: hypostasis, polyeleos, symbol (only in the sense of a symbol of faith), synod (although in dictionaries it is synod). Derivative words from s?mvol and s?nod were not retained by the beginning of the 20th century: symbolic, synodal, synodskiy, synodic.

The letter ъ was written at the end of words after consonants and was not read. As opposed to ь at the end of words, which softens consonants. It’s also official in the word “to examine”. Occurs in the word supersensible. In the word suzhit, Grot ordered not to use it. When writing words with a hyphen - in the usual common words ъ was retained: iz-za, rear-admiral. And when writing borrowed names, ъ could be omitted before the hyphen. (Omitting ъ before the hyphen is Grot’s wish).

Spelling of individual morphemes (prefixes, case endings)

Prefixes ending in -з (iz-, voz-, raz-, roz-, niz-) before the subsequent s were retained z: rasskaz, reason, reunite. The prefixes without-, through-, through- always had an -z at the end: useless, bloodless, tactless, sleeplessness; too much, beyond the stripe.

Instead of the ending -og it was written -ago: red, black.

Instead of the ending -his it was written -yago: blue, third.

(After hissing words, instead of -he, they wrote not -yago, but -ago: elder, fallen, skinny).

The ending -ого was used only in the following cases: if the emphasis fell on it: so? go, lame? go. And also in the words: first, that, this; himself? (but sa?mago).

Instead of the ending of the instrumental case -ой there were two endings - the main (full) -оь and its shortened version -ой. You can notice (but this is not a rule) that when writing two or more words in a row with the ending -оу, the latter is abbreviated to -оу: “in some verbal form.” In modern spelling, on the contrary: -ой is the usual ending, and -оу is its variant. But now -oy is used everywhere, and -oy can only be found in poetry.

Instead of the ending -yu there were two endings - the main one -iyu and its variant -yu.

In the textbook of the early twentieth century (1915) we can see the forms bone(s), cane(s).

In the feminine and neuter gender, instead of the endings -y, -ie, the endings -yya, -iya were used: Russian p?sni, new chairs. The endings -е, -е were used with masculine words: new tables, good houses. When listing words of the feminine and neuter gender, the endings -yya, -iya were used: new sleeps, chairs and dreams. To denote aggregates in which masculine nouns participated, the ending -е, -ie was used: new magazines, books and publications.

In the feminine gender, instead of “they” they wrote (and in some cases pronounced) “he?” (In other genders - “they”).

In the feminine gender, the words “odn?”, “odn?khb”, “odn?m”, “odn?mi” were also used. (In other genders - “one”, “one”, “one”, “one”).

The pronoun “her (her)” in the genitive case was written (and in poetry it could be pronounced) as “her (her)”, but “her (her)” in the accusative case: He took her book and gave it to her, Her Imperial Majesty , her sad villages.

Instead of the word “sama” it was customary to write “most”. She blamed herself. (Using the word “most” in the neuter gender is an error.) (The word “samu” appears in Dahl’s dictionary along with the word “most”, but it was considered more literate to write “most”).

The word “myself” was used only when someone did something himself: I ordered it myself. She decided so herself. It fell on its own. In other cases, instead of the word “sam” they said and wrote “samy”. Is this him? - He's the one. When did he arrive? - He came on the very day of Easter. “The most” - true, real. God is the very truth and the most good, or is it itself? truth and itself? good. Say your own words? his, word for word, authentic. (A very serious mistake when pronouncing these unusual forms of words is to pronounce the ugly “most” instead of the word “most” - this is incorrect. Such errors in stress placement arise from the lack of information about the correct pronunciation).

The word "essence" was a plural form of the verb "is". number. Dill, garlic and carrots are vegetables. This is all the essence of hypotheses and assumptions.. The main vowel sounds in Russian and Church Slavonic languages are: a, u, i.

The rules for word hyphenation were a little more complex than modern ones

Writing and pronunciation. The combination of letters ъ and was pronounced as ы. (It ceased to be used at the beginning of the twentieth century, but is found in old books). The combination of letters iе was sometimes pronounced as e: Iehovah, Ierusalim (Erus. and Jerusalem), Iemen, iena. The combination of letters io was sometimes pronounced as e: iotъ, maiorъ, raionъ. The combination of letters iу was sometimes pronounced as yu: Iudi?ь, Iуliаnъ (but Iuda - Judas). The indicated combinations of vowels with the letter i occur mostly at the beginning of words. The difference in pronunciation before the revolution and now is noticeable only in two cases - Iehovah and Ierusalem (the latter word could be pronounced the same way as now). Note: in modern Russian, in the word yen, we also pronounce the first two vowels with one syllable “je”.

Abbreviations of words. Unlike modern spelling, when abbreviating words, dots were required: S. s. - State Councilor, Doctor of Social Sciences With. - actual state councilor, t.s. - Privy Councilor, D.T.S. - Actual Privy Councilor M.V.D. - Ministry of Internal Affairs, Academician. Com. - Scientific Committee, Min. Nar. Etc. - Ministry of Public Education, Akt. General - Joint-Stock Company.

Superscripts. In pre-revolutionary spelling, it was customary to place emphasis on the word “what”, distinguishing between types of words. The accent marks the pronoun “what?” in the nominative or accusative case to distinguish it from the similar conjunction “what”: - Do you know what? useful for you. You know that teaching is good for you.

Punctuation. At the end of headings, unlike modern spelling, periods were added. Titles and addresses were written with a capital letter: “Sovereign Emperor”, “Medal in memory of the coronation of THEIR IMPERIAL MAJESES”, “HIGHLY APPROVED”, “Your Imperial Majesty”, “Your Honor”.

Note. The word "Sovereign" is an address only to the living emperor. In a 19th-century book they could have printed “the book is dedicated to the Sovereign Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich,” meaning that when this dedication was written, the emperor was reigning. It is customary to speak only of “Emperor” about deceased emperors: Emperor Alexander III, Emperor Nicholas II.

2.2 Peter's reform

A major reform of the Cyrillic alphabet was carried out by Peter I in 1708-1710. Some letters written according to tradition, but not necessary for Russian writing, were abolished: w (omega), y (psi), x (xi), S (zelo). In addition, the style of the letters themselves was changed - they were closer in appearance to Latin ones. This is how a new alphabet appeared, which was called “citizen”, since it was intended for secular texts, in contrast to the Cyrillic alphabet that remained unchanged for Church Slavonic texts. The goal of the reform was to bring the appearance of Russian books and other printed publications closer to what Western European publications of that time looked like, which were sharply different from the typically medieval-looking Russian publications, which were typed in Church Slavonic font - semi-ustav. In June 1707, Peter I received samples of medium-sized font from Amsterdam, and in September - prints of a trial set in large and small sized fonts. A printing press and other printing equipment were purchased in Holland, and qualified typographers were hired to work in Russia and train Russian specialists. January 01, 1708. Peter I signed a decree: “...sent by the land of Galana, the city of Amsterdam, book printing craftsmen... to print the book Geometry in the Russian language in those alphabet... and to print other civil books in the same alphabet in the new alphabet...”. The first book typed in the new font, “Geometry Slavenski zemmerie” (geometry textbook), was printed in March 1708. After the publication on January 25, 1708 of “Geometry” and “Butts of how different compliments are written...” Ivan Alekseevich Musin-Pushkin (1661-1729) asks the tsar to “make a decree” on what other books to print in “newly published” letters, and at the end of that same year sends him “...the alphabet of the newly corrected letters.” Peter I was dissatisfied with these corrections and, in a letter dated January 4, 1709, proposed making a number of new corrections. In response to this, on January 18, 1709, Musin-Pushkin wrote to the Tsar that as soon as corrections were made to the alphabet, he would send him a corrected sample, and on September 4 of the same year he sent samples of new letters to Peter I for approval. In all likelihood, this was the last, known version of the civil alphabet, which was approved by Peter I on January 29, 1710. On the back of the binding of the approved sample of the alphabet, in a free space, Peter I wrote in his own hand: “In these letters, print historical and manufacturing books, and those that are underlined should not be used in the books described above.” On the first page of the alphabet, where the initial letters of the alphabet are printed, the date of approval is indicated below in red ink: “Given in the year of the Lord, January 1710, on the 29th day.” The alphabet has the title: “Image of ancient and new Slavic printed and handwritten letters.” The handwritten version of the civil font ("civil letter") was the last to develop - only in the second half of the 18th century. Previously, cursive writing of the old Moscow model was used. Until 1867, Citizen was the only script in the world other than Latin that was distributed in three parts of the world - Europe, Asia and America (Alaska). “Petrine and Bolshevik reforms of spelling, as well as the calendar, were only the final stages of secularization, secularization of the once sacred in its very essence writing, which from a tool for human communication with God and the subtle world turned into a simple tool for the everyday activities of people, including and household. After all, what else can you expect from inscriptions on fences, toilet doors and on the packaging of ordinary goods?"

2.3 Reform of 1917

spelling reform Cyrillic letter

As a result of the reform of 1917-1918, the letters “yat”, “fita”, “I” were excluded from Russian writing, the spelling of Ъ at the end of words and parts of complex words was canceled, and some spelling rules were changed, which is inextricably linked with the October Revolution. The first edition of the decree introducing a new spelling was published in the Izvestia newspaper less than two months after the Bolsheviks came to power - December 23, 1917 (January 5, 1918, new style). The reform of the “citizenship” of Peter I is changing, and the new reform is aimed at saving students’ efforts.

In fact, the language reform was prepared long before October 1917, and not by revolutionaries, but by linguists. Of course, not all of them were alien to politics, but here is an indicative fact: among the developers of the new spelling there were people with extreme right-wing (one might say counter-revolutionary) views, for example academician A.I. Sobolevsky, known for his active participation in the activities of various kinds of nationalist and monarchist organizations. Preparations for the reform began at the end of the 19th century: after the publication of the works of Yakov Karlovich Grot, who for the first time brought together all the spelling rules, the need to streamline and simplify Russian spelling became clear. Add about Grotto.

It should be noted that thoughts about the unjustified complexity of Russian writing occurred to some scientists back in the 18th century. Thus, the Academy of Sciences first tried to exclude the letter “Izhitsa” from the Russian alphabet back in 1735, and in 1781, on the initiative of the director of the Academy of Sciences Sergei Gerasimovich Domashnev, one section of “Academic News” was printed without the letter Ъ at the end of words (in other words, separate examples of “Bolshevik” spelling could be found more than a hundred years before the revolution!).

In 1904, an Orthographic Commission was created at the Department of Russian Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences, which was tasked with simplifying Russian writing (primarily in the interests of the school). The commission was headed by the outstanding Russian linguist Philip Fedorovich Fortunatov (in 1902 he was elected director of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, moved to St. Petersburg and received an academic salary; in the 70s of the 19th century he founded the department of comparative historical linguistics at Moscow State University). The spelling commission also included the greatest scientists of that time - A.A. Shakhmatov (who headed the commission in 1914, after the death of F.F. Fortunatov), I.A. Baudouin de Courtenay, P.N. Sakulin and others.

The results of further work of linguists were already assessed by the Provisional Government. On May 11 (May 24, new style), 1917, a meeting was held with the participation of members of the Spelling Commission of the Academy of Sciences, linguists, and school teachers, at which it was decided to soften some provisions of the 1912 project (thus, the commission members agreed with A.A. Shakhmatov’s proposal to preserve soft sign at the end of words after hissing ones). The reform was possible because it concerned only the written language. The result of the discussion was the “Resolution of the meeting on the issue of simplifying Russian spelling,” which was approved by the Academy of Sciences. The reform was needed because most of the population was illiterate or semi-literate. Linguists believed that if you give a simplified Russian language, then there will be no lagging behind in schools. But it turned out that the lagging behind remained the same (Shcherba). Expectations were not met, since learning depends on the availability of abilities; not everyone can be taught something, and this is the norm. But they didn’t know about it then.

The new spelling was introduced by two decrees. In the first, signed by the People's Commissar of Education A.V. Lunacharsky and published on December 23, 1917 (January 5, 1918), “all government and state publications” were ordered from January 1 (Old Art.), 1918, “to be printed according to the new spelling.” Since the new year (according to Art. Art.), the first issue of the official press organ of the newspaper "Newspaper of the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government" was published (as well as subsequent ones) in a reformed spelling, in strict accordance with the changes provided for in the Decree (in particular, with using the letter “ъ” in the separating function). However, other periodicals in the territory controlled by the Bolsheviks continued to be published, mainly in pre-reform versions; in particular, the official organ of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Izvestia, limited itself to only not using “ъ”, including in the dividing function; The party organ, the newspaper Pravda, was also published.

This was followed by a second decree dated October 10, 1918, signed by Deputy People's Commissar M.N. Pokrovsky and the manager of the Council of People's Commissars V.D. Bonch-Bruevich. Already in October 1918, the official bodies of the Bolsheviks - the newspapers Izvestia and Pravda - switched to the new spelling.

In practice, the state authorities quickly established a monopoly on printed materials and very strictly monitored the implementation of the decree. A frequent practice was to remove from printing desks not only the letters I, fita and yatya, but also b. Because of this, the writing of an apostrophe as a dividing mark in place of b (under oh hell Yutant), which began to be perceived as part of the reform (although in fact, from the point of view of the letter of the decree of the Council of People's Commissars, such writings were erroneous). However, some scientific publications (related to the publication of old works and documents; publications, the collection of which began even before the revolution) were published according to the old spelling (except for the title page and, often, prefaces) until 1929.

Pros of reform.

The reform reduced the number of spelling rules that had no support in pronunciation, for example, the difference in genders in the plural or the need to memorize a long list of words spelled with “yat” (moreover, there were disputes among linguists regarding the composition of this list, and various spelling guidelines sometimes contradicted each other ). Here we need to see what this nonsense is all about.

The reform led to some savings in writing and typography, eliminating Ъ at the end of words (according to L.V. Uspensky, the text in the new orthography becomes approximately 1/30 shorter - cost savings).

The reform eliminated pairs of completely homophonic graphemes (yat and E, fita and F, I and I) from the Russian alphabet, bringing the alphabet closer to the real phonological system of the Russian language.

Criticism of the reform.

While the reform was being discussed, various objections were raised regarding it:

no one has the right to forcibly make changes in the system of established spelling... only such changes are permissible that occur unnoticed, under the influence of the living example of exemplary writers;

there is no urgent need for reform: mastering spelling is hampered not so much by the spelling itself, but by poor teaching methods...;

reform is completely unfeasible...:

It is necessary that simultaneously with the implementation of the spelling reform in school, all school textbooks should be reprinted in a new way...

and tens and even hundreds of thousands of home libraries... often compiled with the last pennies as an inheritance to children? After all, Pushkin and Goncharov would be to these children what pre-Petrine presses are to today’s readers;

it is necessary that all teaching staff, immediately, with full readiness and with full conviction of the rightness of the matter, unanimously accept the new spelling and adhere to it...;

it is necessary... that bonnies, governesses, mothers, fathers and all persons who provide children with initial education begin to study the new spelling and teach it with readiness and conviction...;

Finally, it is necessary that the entire educated society greet the spelling reform with complete sympathy. Otherwise, discord between society and school will completely discredit the authority of the latter, and school spelling will seem to the students themselves as a distortion of writing...

From this the conclusion was drawn:

All this leads us to assume that the planned simplification of spelling entirely, with the exclusion of four letters from the alphabet, will not come into practice in the near future.

Despite the fact that the reform was developed without any political goals, due to the fact that it was the Bolsheviks who introduced it, it received a sharply negative assessment from opponents of Bolshevism. Since the Soviet government was illegitimate in their eyes, they refused to recognize the change in spelling.

Ivan Bunin, who was not only a famous poet and writer, but also an honorary academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, said this:

I will never accept Bolshevik spelling. If only for one reason: the human hand has never written anything similar to what is now written according to this spelling.

2.4 Khrushchev reform

The appearance of an officially adopted set of rules for spelling and punctuation and a spelling dictionary was preceded by seven projects. In 1951, the commission prepared the latest edition of the code, and a large spelling dictionary was compiled at the Academic Institute of Linguistics under the leadership of Sergei Obnorsky. This project was widely discussed in periodicals. As a result, two main documents appeared: published in 1955 and approved in 1956 by the Academy of Sciences, the Ministry of Education of the RSFSR and the Ministry of Higher Education, “Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation” - the first officially adopted set of rules, mandatory for everyone writing in Russian, and “Spelling Dictionary of the Russian Language with the Application of Spelling Rules” 1956 for 100 thousand words, edited by Sergei Ozhegov and Abram Shapiro. The 1956 code did not become a spelling reform, since it did not affect its fundamentals, but established the norms of Russian spelling and punctuation. This is the first set of clearly formulated and scientifically based rules in the history of Russian spelling. Despite all its importance, this code did not exhaust all the possibilities for improving Russian spelling. The code was not a reform.

By the way, no one has seen these “Rules...” for a long time. They haven't been reprinted for a very long time. Instead, well-known manuals on Russian spelling were published by Dietmar Elyashevich Rosenthal and his co-authors, who somehow developed the provisions of these “Rules...” and interpreted them.

2.5 1964 project

After the streamlining of 1956, it became more noticeable what improvements could still be made to Russian spelling. Actually, the project was dedicated to using to the fullest possible extent the principle that underlies all changes in Russian spelling in the twentieth century and is present in most spellings. In May 1963, by decision of the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences, a new spelling commission was organized to eliminate “contradictions, unjustified exceptions, difficult to explain rules” of spelling, the chairman of which was the director of the Institute of Russian Language of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Viktor Vinogradov, and the deputies were the actual author of the reform, Mikhail Panov. and Ivan Protchenko, a kind of representative of party bodies in linguistics. What was unusual was that the commission, in addition to scientists, teachers and university professors, included writers: Korney Chukovsky, later Konstantin Fedin, Leonid Leonov, Alexander Tvardovsky and Mikhail Isakovsky.

The project, prepared over two years, included many of the previously developed but not accepted proposals, in particular:

Leave one dividing sign b: blizzard, adjutant, volume.

After q, always write i: circus, gypsy, cucumbers.

After zh, ch, sh, shch, ts write under the stress o, without stress - e: yellow, yellow.

After f, w, h, sch do not write b: wide open, hear, night, thing.

Eliminate double consonants in foreign words: tennis, corrosion.

Simplify the writing n - nn in participles.

Combinations with gender should always be written with a hyphen.

Remove exceptions and write from now on: jury, brochure, parachute; little darling, little babe, little babe; worthy, hare, hare; wooden, tin, glass.

In general, the proposals were quite linguistically justified. Of course, for their time they seemed quite radical. The main mistake of this attempt at reform was this: as soon as these proposals were put forward, they were widely published in 1964 in full detail, primarily in the magazines “Russian Language at School”, “Questions of Speech Culture” and in the “Teacher's Newspaper” , but also in the public newspaper Izvestia. In other words, they brought it up for public discussion. For six months, if not more, Izvestia published reviews - almost all negative. That is, the public did not accept these proposals. This coincided with the departure of N.S. Khrushchev, with a sharp change in the political situation in the country. So they soon tried to forget about this failed reform. And it still turned out that the proposals were not linguistically justified, people were not prepared for such changes.

2.6 Reform of the 20s

In 1988, by order of the Department of Literature and Language of the USSR Academy of Sciences, the spelling commission was recreated with a new composition. Since the end of 2000, Professor Vladimir Lopatin became its chairman. The main task of the commission was to prepare a new set of rules for Russian spelling, which was supposed to replace the “Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation” of 1956. Back in 1991, under the leadership of Lopatin, the 29th, corrected and expanded, edition of the “Spelling Dictionary of the Russian Language” appeared, which had not been supplemented for 15 years and was published only in stereotypical editions (the last supplemented was the 13th edition of 1974) . But from the very beginning of the 1990s, the task was set of preparing a fundamentally new - both in volume and in the nature of the input material - a large spelling dictionary. It was published in 1999 under the title “Russian Spelling Dictionary” and included 160 thousand vocabulary units, exceeding the previous volume by more than one and a half times. A year later, the “Project “Code of Russian Spelling Rules” was released. Spelling. Punctuation"".

The new code was intended to regulate the spelling of linguistic material that arose in the language of the second half of the twentieth century, eliminate the shortcomings that were revealed in the 1956 code, and bring spelling into line with the modern level of linguistics, offering not only rules, as was in the 1956 code, but also their scientific justification. What was also new was that variability in some spellings was allowed. Here are a few innovations:

Write common nouns with the EP component without the letter Y before E: conveyor, stayer.

Write brochure and parachute, but julienne, jury, monteju, embouchure, pshute, fichu, schutte, schutzkor.

Expand the use of the separative Ъ before the letters E, Ё, Yu, Ya: art fair; military lawyer, state language, children's school, foreign language.

The rule about НН and Н in the full forms of passive past participles: for formations from imperfective verbs, spellings with one N are accepted. For formations from perfective verbs, single spellings with two N are retained.

Fearing a repeat of history with the 1964 project, members of the spelling commission did not report the details until the time came, but did not take into account the fact that the public in the mid-1960s had already been partially prepared by the recent code of 1956 and the discussion in pedagogical periodicals. Discussion in the general press began in 2000, and since it was initiated by non-specialists, members of the commission and working group had to take an explanatory and defensive position. This discussion, unfavorable for the new project, continued until approximately the spring of 2002. In this situation, the directorate of the Institute of the Russian Language had already decided not to submit the compiled code and dictionary for approval, and therefore the commission abandoned the most striking proposals, leaving mainly those that regulated the writing of new words.

Finally, in 2006, the reference book “Rules of Russian Spelling and Punctuation” was published, edited by Vladimir Lopatin, which was offered to specialists for discussion, without “radical” changes. Thus, the issue of changes in modern spelling is not yet closed. In 2005, a new, corrected and expanded edition of the “Russian Spelling Dictionary” was published with a volume of about 180 thousand words. This normative dictionary is approved by the Academy of Sciences, in contrast to the “Rules,” which must be approved by the Russian government, and is already mandatory.

It turns out that the reform failed again for reasons of language policy. Linguists proceeded from a model of language policy that considers written language to be completely controllable on the basis of certain postulates. But it is language that must govern linguistics. Science must be controlled, not its object.

2.7 Later reforms

Under V.V. Putin’s reform ideas also failed, but they found their way into dictionaries: confirm or refute. The reform is carried out secretly by preparing dictionaries where you can say “black coffee”. And these dictionaries are included in the recommended list of dictionaries. The regulation of language is closely related to the regulation of public opinion.

Minister of Education A.A. Fursenko, following the Unified State Exam and the self-supporting basis of schools, dealt another blow to Russian education - he put into effect on September 1 Order No. 195 of June 8, 2009 “On approval of the list of grammars, dictionaries and reference books.”

According to this order, when resolving various controversial issues relating to the use of the Russian language as the state language of the Russian Federation, it is necessary to use an approved list of grammars, dictionaries and reference books.

Currently, this list includes only four books published by the same publisher:

Spelling dictionary of the Russian language. Bukchina B.Z., Sazonova I.K., Cheltsova L.K.

Grammar dictionary of the Russian language: Inflection. Zaliznyak A.A.

Dictionary of accents of the Russian language. Reznichenko I.L.

Large phraseological dictionary of the Russian language. Meaning. Use. Cultural commentary. Telia V.N.

At the same time, this list does not include such famous and popular dictionaries edited by Lopatin, Dahl, Ozhegov.

Innovations. Thus, the word “coffee” can now be used in both the masculine and neuter gender. In the word “agreement”, the emphasis can now be placed on the first syllable - “agreement”. The word “barzha” can be replaced with the word “barzhA”, “yogurt” is now equal to “yogurt” and other horror. Here are some examples:

Conclusion