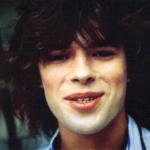

Born on August 17, 1926, Yangzhou, eastern Jiangsu Province. His grandfather Jiang Shixi was a merchant and doctor of traditional Chinese medicine. Little is known about his father, Jiang Shijun. According to some reports, he was a collaborator and worked in the puppet government in Nanjing (from 1937 to 1945 Jiangsu was occupied by Japan). According to the official biography of Jiang Zemin, in 1939, with the consent of his parents, he was adopted by the widow of his uncle, the communist Jiang Shangqing. It is reliably known that Jiang’s family belonged to the intelligentsia, along with modern ones, he received the basics of a traditional Confucian education: he studied music, versification and calligraphy.

In 1947, Jiang Zemin graduated from the electrical engineering department of one of the country's leading universities - Jiaotong University (Shanghai). Even before graduating from university, he began working at a food industry enterprise in Shanghai, subsequently became deputy director of a soap factory, and then headed the electrical equipment department of the Shanghai Design Bureau under the First Ministry of Mechanical Engineering of the People's Republic of China.

Since 1946 - member of the Communist Party of China (CCP).

In 1955, he completed an internship at the 1st State Automobile Plant named after I.V. Stalin in Moscow (today - the plant named after I.A. Likhachev, ZIL), after which until 1962 he worked at the first automobile manufacturing plant in China in Changchun (Jilin province, built with the assistance of the USSR).

In 1962-1980 He worked at various enterprises and research institutes in Shanghai and Wuhan, as well as at the International Relations Department of the First Ministry of Mechanical Engineering in Beijing.

Since 1980, Jiang Zemin has held senior positions in the State Committees for Import-Export Control and Foreign Investment Affairs. During this period, he oversaw the creation and operation of China's first special economic zone (SEZ) Shenzhen.

In 1982-1985. - Minister of Electronics Industry of the People's Republic of China.

In September 1982 he was elected a member of the Central Committee, in November 1987 - a member of the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee.

In 1985 he became the mayor of Shanghai, and in 1987 - secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Committee of the CPC. As the head of the country's largest city, he contributed to reforms and policies to expand the city's connections with the outside world, and mitigated the severity of the housing problem. When anti-government unrest began in Shanghai in April 1989, Jiang Zemin was able to resolve the conflict without sending troops (while in Beijing, student protests in Tiananmen Square were suppressed with the help of the army). Jiang's actions in this situation were noted at the highest level: he was chosen as the successor to the de facto leader of the PRC - Chairman of the Central Military Council of the PRC Deng Xiaoping.

Since June 1989, Jiang Zemin has been a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee. In November of the same year, he became chairman of the Military Council of the CPC Central Committee, in April 1990 - chairman of the Central Military Council of the PRC, on March 27, 1993 - chairman of the PRC. Thus, Jiang Zemin headed the so-called. third generation of Chinese leaders (after Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping). The official Chinese press called him the “core” of the country’s collective leadership.

As Chairman of the People's Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping consistently pursued the course of building "socialism with Chinese characteristics", which meant carrying out liberal reforms in the economy while maintaining party control over the political sphere. During the period when Jiang Zemin headed the party and state, China became one of the world's leading powers, creating one of the most stable and dynamic economies. At this time, such events as reunification with Hong Kong (Hong Kong) in 1997 and Macao (Macau) in 1999, accession to the WTO in 2001, and successful overcoming the consequences of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998 occurred.

In 2001, Jiang Zemin came up with the idea of the “three branches”, which allowed Chinese private entrepreneurs to join the party. This principle was enshrined in the charter of the CPC, which in fact ceased to be exclusively a party of “workers and peasants.”

Jiang Zemin played an important role in improving relations between Russia and China, the result of which was the signing of the Treaty of Good Neighbourliness, Friendship and Cooperation during his visit to Russia in July 2001. He was also one of the initiators of the creation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, 2001).

On November 14, 2002, Jiang Zemin officially resigned as General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee. On March 15, 2003, he also left the highest government post - Hu Jintao, a representative of the fourth generation of Chinese leaders, was elected Chairman of the People's Republic of China. The transfer of power was completed in March 2005, when Hu Jintao replaced Jiang Zemin as chairman of the Central Military Commission.

Jiang Zemin is considered the head of the "Shanghai clique" - a group of high-ranking CCP officials whose careers began in Shanghai while he was the city's mayor. The clan's influence sharply declined after the arrest of the secretary of the Shanghai City Party Committee, Chen Liangyu, on corruption charges in September 2006 and subsequent personnel purges. After Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power, a number of individuals considered to be Jiang Zemin's protégés were also arrested, including former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang and former vice-chairmen of the Central Military Commission Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong.

He speaks Russian, Romanian (he worked in Romania for two years as the head of a group of specialists) and English, reads Japanese and French.

Jiang Zemin's wife, Wang Yeping, previously headed the Shanghai Electrical Engineering Research Institute. The couple have two sons.

Jiang Zemin plays the Chinese bamboo flute, piano, harmonica, and loves to perform arias from Chinese operas and Soviet hits of the 1940s-1950s. Knows a lot of Russian sayings. He is a great connoisseur of Chinese classical literature, especially loves ancient Chinese poets of the Tang and Song dynasties, whom he often quotes. Writes poems.

Born on August 17, 1926 in Yangzhou, Prov. Jiangsu in a family of hereditary intellectuals. My grandfather was a doctor who practiced Chinese traditional medicine and was fond of painting and calligraphy. My father wrote poetry, published patriotic magazines during the anti-Japanese war, and joined the Communist Party, which was underground. At the age of 28 he died in an armed battle. Jiang Zemin followed in his father's footsteps. In the 40s, while studying at the prestigious Shanghai University of Transport and Communications, he became involved in underground work. In 1946 he joined the CPC.

After the formation of the People's Republic of China, Jiang worked for almost 30 years in the Ministry of Mechanical Engineering, where he rose from a low-level manager to the director of a large research institute. As Russian experts note, during the years of the “cultural revolution” he underwent “labor education” as an ordinary employee of a research institute. His uncompromising attitude towards leftism was noticed, and at the end of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Zemin was sent to Shanghai as part of a working group of the Party Central Committee to investigate the crimes of the Gang of Four.

In the early 80s. Jiang was the Minister of Electronics Industry and promoted the introduction of many advanced foreign technologies and established connections with influential members of the military-industrial complex. He is very familiar with the creation of special economic zones and attracting foreign capital to the country. In the eighties, he visited free trade zones in more than ten countries.

In 1985-1989 he worked in Shanghai as mayor and then secretary of the party committee. The skills of competent communication acquired through experience helped him firmly occupy his political niche.

In power

He headed the CPC in 1989, when, after the dispersal of student demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, Zhao Ziyang, was relieved of his post and placed under house arrest, having supported the demands of the protesters about the need for political freedoms in the PRC.

At the suggestion of the then leader of the People's Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping, the party was headed by the head of the Shanghai party organization, Jiang Zemin. At first he was considered a temporary figure, but he quickly managed to take control of the party, government and army, and in 1993 became chairman of the People's Republic of China.

In his policy he continued the reforms begun by Deng Xiaoping. Having led China, which had just begun the struggle for world markets, Jiang Zemin brought the PRC economy to seventh place in the world. Under Jiang Zemin, China joined the WTO, strengthened its economic and military potential, made a bid for leadership in the Asia-Pacific region (APR), hosted the ASEAN summit in Shanghai, and won a bid to host the Olympic Games in 2008.

Best of the day

Despite the resistance of conservatives in the ranks of the CPC, Jiang Zemin managed to make his theory of “three representations” part of the party program, which equalized the political rights of the intelligentsia with workers and peasants and opened the way to the party for private entrepreneurs.

In 2002−2005, as a result of the struggle for power in the party and state leadership, the PRC lost all top party, state and military posts to Hu Jintao.

The Soviet Union, as the birthplace of the ideology of communism, occupies a special place in the political biography of Jiang Zemin.

In the 50s, Jiang trained in the USSR at the Stalin Automobile Plant. It was then that he developed a special Soviet mentality. Jiang speaks Russian, knows proverbs and sayings, and sings songs from the 40s and 50s. In the 90s, already in the rank of Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party, he visited Moscow. And finally, in 1998, the first “meeting without ties” took place in the history of Chinese diplomacy. First of all, he met with those people with whom he worked at ZIS in 1955. It is clear that among the worries of state he does not forget his old friends.

In 1997, having signed a document with President Yeltsin on the world order in the 21st century and a multipolar world based on equal cooperation and not on confrontation between blocs, he went to Yasnaya Polyana. He had long dreamed of visiting the estate of his favorite writer. The chairman asked his Russian hosts not to lecture him about Tolstoy, whose works he knew very well. He was attracted by the philosophical foundations of the classic's work.

Family

Jiang Zemin is married. His wife is Wang Yeping, whom he married in 1948, also from Yangzhou, Prov. Jiangsu. Has two sons - Jiang Mianheng and Jiang Jinkang.

Hobbies

He speaks English and Russian and is a lover of literature and music.

Writes books and memoirs. On August 11, 2006, the book “Selected Works of Jiang Zemin” was published, the start of sales of which was widely covered on central television. Through the efforts of one of the teachers in China, the poems of Chinese President Jiang Zemin are included in a school textbook on literature. Jiang Zemin tried his luck in the field of poetry in 1991, when he dedicated a poem to the harsh winter in northwest China. And he composed the last poem during his ascent to the Yellow Mountain - one of the sacred peaks for the inhabitants of the Celestial Empire. In 2001, the Chinese leader wrote at least three poems, one of which he dedicated and presented to Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Jiang Zemin is also known as a good singer of songs, which he sometimes demonstrates in duets with great singers or with foreign colleagues. For example, the famous Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti believed that Jiang could well become a major opera star. According to the singer, the Chinese leader invited him, along with Jose Correras and Placido Domingo, to have lunch with him after their concert in Beijing. “We all started singing,” said the Italian, “and the Chinese president sang the duet “O sole mio” with me.” Pavarotti was amazed by Jiang Zemin's abilities.

Former head of the Communist Party of China Jiang Zemin attends the closing session of the 18th National Party Congress at the Great Hall of the People on November 14, 2012 in Beijing. At this congress, Xi Jinping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party, who has been prosecuting members of Jiang's faction on corruption charges for 19 months. Photo: Feng Li/Getty Images

The days are numbered. The man who dominated Chinese politics for more than twenty years is now under investigation in his hometown of Shanghai.It has been repeatedly reported that the anti-corruption investigation team of Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has begun work in Shanghai. Information that this investigation is quite serious appeared on August 11 in a short notice on the official website of the Shanghai Prosecutor's Office, the department in charge of investigating and prosecuting crimes.

Extremely successful businessman Wang Zongnan, president of Bright Food Group, was arrested for bribery and embezzlement. These are crimes that Wang will be tried for, but his real crime is having close ties with former (CCP) chief Jiang Zemin and Jiang's son, Jiang Mianheng.

Shanghai was the springboard for Jiang Zemin's great political ambitions and formed the foundation of his power.

From 1985 to 1989, Jiang was the head of the party in Shanghai. Confronted with a persistent democracy movement in 1989, Deng Xiaoping was impressed by Jiang's brutal handling of dissidents in Shanghai while many other CCP leaders stood by.

After General Secretary Zhao Ziyang was removed from office for his sympathy for those students, Deng took Jiang Zemin to Beijing. Once in power, Jiang ruthlessly hunted down and punished dissidents who fled from tanks on the night of June 4.

After taking power in Beijing, Jiang promoted previously unheralded party workers from Shanghai to positions of influence throughout the party. They formed the core of a vast web of connections that Jiang used to dominate Chinese politics for more than 20 years.

Make Jiang a target

Over the past 19 months, CCP chief Xi Jinping has purged Jiang's top allies in a sweeping anti-corruption campaign.The campaign seemed to culminate with the July 29 announcement of a formal investigation into the former security chief. The idea that the fall of Zhou would end the purges in the party was quickly dispelled.

Immediately after the announcement of Zhou, the CCP mouthpiece People's Daily published a commentary entitled "Removing the big tiger Zhou Yongkang is not the end of the anti-corruption movement." The article noted that Zhou was appointed as a high-ranking official from above. It is common knowledge that Zhou promoted Jiang Zemin.

Although the article was quickly deleted, it remained online long enough to be copied and widely disseminated throughout China.

Two weeks earlier, The Epoch Times reported that Jiang Zemin's chief adviser. If the anti-corruption campaign is anything other than a purge, then logically the next target is Jiang Zemin himself. All other large tigers have already been removed.

Wang Zongnan's arrest last week leaves Jiang very vulnerable. If Jiang is unable to save Wang, who is in Shanghai, from arrest, then he has been deprived of power in his own deepest stronghold. There is an open field in front of Xi to pursue Jiang Zemin.

If everything is going as planned, then just as the Central Discipline Inspection Commission has done in thousands of previous cases elsewhere in China, it is now prowling around Shanghai, building a case, working from the outside in. The Commission pins down the weakest, those on the periphery, making sure these targets expose their connections to those closer to the center, and then advances step by step until the ultimate target is surrounded and helpless.

Stephen Gregory The Epoch Times

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

According to the book Conversations with Zhao Ziyang, who was under house arrest, published in Hong Kong, at the 16th Party Congress, Hu Jintao was not given the title of "core" of the party as a result of Jiang Zemin's careful plans. /website/

Zong Fengming, the author of this book, retired in 1986. Before that, he was the party secretary of Beijing Aviation and Astronautics University, and later worked part-time as a researcher at the Economic Reform Research Society. From July 1991 to October 2004 he had the status of a qigong master. Zong Fengming repeatedly visited the former Secretary General of the People's Republic of China Zhao Ziyang, who was under life sentence house arrest. These two were fellow countrymen and comrades. Later, Zong wrote a book based on conversations with Zhao Ziyang and, despite opposition from the Communist Party, published it in Hong Kong.

Zhao Ziyang: Jiang Zemin carefully planned to prevent Hu Jintao from becoming the 'core'

The book says that shortly after the 16th Party Congress, in 2002, Zhao Ziyang, discussing this congress with Zong Fengming, said: “This time, when the position was proclaimed, they only called him the general secretary, but did not call him the head, did not call him the chief, Moreover, they were not called the “core”. The Secretary General is a position, not a position. It looks like this convention was carefully planned. Some say that this congress turned out well, that this is development. How can this be progress? The Central Committee of the Politburo at one time decided that retirement should occur at 70 years of age. This time, Li Ruihuan (former member of the Politburo Standing Committee) retired, although he is 68 years old, but Jiang Zemin, who is over 70 years old, did not retire. And no one talks about it openly. That's what's amazing."

Du Rongsheng (former head of the Central Laboratory for the Study of Chinese Villages and the Research Center for Rural Development under the State Council of the People's Republic of China) and Li Rui (former secretary of Mao Zedong) believed that everything Jiang Zemin did served the purpose of maintaining the status quo in the reign and retaining power . Everything else is cliche polite phrases.

The book also tells that Zhao Ziyang once told Zong Fengming: “This time, at the 16th Party Congress, Jiang Zemin fought hard to remain the chairman of the military council. This created a very bad precedent in the history of the CCP. If he did this, then others can too. This is not just a question of the desire for power, but a regression of the entire system. In the past, Deng Xiaoping simultaneously and semi-retired while retaining his position as Chairman of the Military Council. This was due to historical reasons. He had the appropriate competence and high authority. But in the case of Jiang Zemin, this is not the case. He has never been a military man for a single day (in his life) and has never commanded a military operation, but he is being trumpeted as a military specialist. You truly don't know whether to cry or laugh. And this time, the leadership of the Politburo Standing Committee approved nine members of the Standing Committee. This also rarely happened in history (it always included seven people).”

Was the “Special Initiative” at the XVI Congress prepared in advance?

At the 16th CPC Congress, Hu Jintao officially replaced Jiang Zemin as Secretary General of the CPC. According to common sense and the generally accepted rules of the CCP, he should have simultaneously succeeded him as chairman of the military council. However, at the XVI Congress a performance was staged that essentially represented a military coup.

Before this, the media reported that on November 13, 2002, in the presidium of the 16th CPC Congress at the fourth meeting of the Standing Committee, Zhang Wannian, to whom Jiang Zemin promised the post of the next defense minister, unexpectedly pinned Hu Jintao to the wall, saying that 20 members of the presidium (all without exception military ) jointly signed a “special initiative” that proposes leaving Jiang Zemin as chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) of the Communist Party for a new term.

After Zhang Wannian's speech, Li Lanqing (Vice Premier under Jiang Zemin) and Liu Huaqing (Chinese admiral, "father of the modern Chinese navy") declared that they fully supported this "special initiative." Only then did everyone present at the meeting realize that this was all a secretly planned performance in advance. The atmosphere in the meeting room immediately became extremely tense.

Hu was then forced to express his position and say: “I fully approve of the proposal of Zhang Wannian, Guo Boxiong, Cao Gangchuan and the other 20 like-minded people.”

After the presidium approved the “special initiative,” Wan Li (a CCP veteran who held numerous high positions) and five other people who were on vacation were notified of its contents.

After Wan Li heard this news, he was overcome with anger. He slammed his fist on the table, scolding Jiang Zemin, and walked out of the Presidium Standing Committee in protest.

The news reported that this was a staged, deliberate, military coup, and behind the scenes a military coup planned by Jiang Zemin.

This coup d'etat is consistent with the “careful plan” that Zhao Ziyang spoke of at the time.

Why Hu Jintao did not become the “core”

At the 16th Congress, Hu Jintao not only did not gain control of the army, but also did not receive the title of “core” (leader). One media report said that after Jiang Zemin left the post of general secretary, he forbade Chinese media to refer to Hu Jintao as party leader.

At one time, Deng Xiaoping called Jiang Zemin the “core”.

On June 16, 1989, on the 12th day after the Tiananmen massacre, Deng Xiaoping and Yang Shangkun, Wan Li, Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, Li Ruihuan and other representatives of the new Communist Party leadership at a meeting said: “Any ruling group a leader (“core”) is needed. Without it, management is not trustworthy.”

At that meeting, Deng Xiaoping officially introduced the concept of “core”. That is, the first “core” was Mao Zedong, the second was him, and the third was Jiang.

After the Tiananmen massacre that year, Deng Xiaoping had no choice but to agree that Jiang Zemin would replace Zhao Ziyang. However, Deng constantly had concerns about Jiang's appointment. He saw Jiang's unprincipled character. To prevent Jiang from usurping power in the future, Deng Xiaoping, although he resigned as chairman of the Central Military Commission in November of that year, still enjoyed the exclusive right that the “secret decree” provided.

At the XIV Congress of the CPC, he took two actions: 1) appointed Hu Jintao to become the fourth successor, and thereby deprived Jiang of the right to appoint his heir; 2) appointed Lu Huaqing, who had exceeded the age limit for military service, to the post of member of the Standing Committee, so that he, together with the vice-chairman of the military council Zhang Zhen, would control the army until the moment Hu Jintao safely took office.

In the early years, Jiang Zemin did not dare to act recklessly. And after Deng Xiaoping was largely abandoned, Jiang began to hatch plans to create a “Jiang core.”

Chinese soldiers carry flowers to a sculpture of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping to mark his 110th birthday on August 21 in Hong Kong. Photo: Lam Yik Fei/Getty Images

On February 19, 1997, Deng Xiaoping died of illness. After his death, Jiang's henchmen immediately, on behalf of the CPC Central Committee, the Standing Committee of the NPC, the State Council, the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference and the Central Military Commission, published an “Address to the entire Party, the entire army and all the people of the entire country,” in which Jiang Zemin was declared the leader of the party.

Jiang Zemin spoke loudly about himself as the “core” after July 1999. In November, during a conversation with the leadership of the army, he unexpectedly focused attention on his role as a “core” and at the same time added that “there must certainly be a core in the Communist Party, this is a historical pattern.” The fact that after November 1999, Jiang Zemin began to trumpet his “core” status everywhere is inextricably linked with the repression against , which he began in the same year.

On July 20, 1999, Jiang Zemin, regardless of the opinions of others, initiated the suppression of Falun Gong, even though it was a very unpopular decision. After this, Jiang, on the one hand, began to use the officials' desire to get rich and make a career to force them to persecute Falun Gong throughout the country. On the other hand, by starting to advertise himself to the public as the “core” on a large scale, Jiang wanted to intimidate the “princes” so that in the face of such a big political problem, they would hear only his voice. The goal was to have all high-ranking officials obey his dictates and actively persecute Falun Gong.

Due to the fact that there was some internal animosity between Jiang Zemin and Deng Xiaoping after 1989, and Hu Jintao was Deng Xiaoping's designated future successor to Jiang as Secretary General of the CCP, and due to the difference of opinion between Jiang and Hu regarding Falun Gong, Hu Jintao was absolutely an unacceptable candidate for Jiang.

The fact that Hu Jintao did not create the Hu Core means that Jiang Zemin did not truly give him power.

Political commentator Li Linyi says that during the years when Jiang Zemin persecuted Falun Gong, Hu Jintao did not want to bear responsibility for Jiang's guilt and did not want to be shackled by Jiang on the Falun Gong issue. At the same time, Jiang did not trust Hu Jintao and, more importantly, was afraid that after he transferred the status of the “core” to Hu, he, Jiang, would face retribution. Therefore, Jiang Zemin planned to make Hu Jintao a formal figure and distribute power equally among the then nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee, thereby dispersing Hu's power as much as possible.

Discussions about the "core"

Since 2016, the term “core” has again been actively discussed in CCP newspapers. At the moment, the secretaries of the party committees have already called more than ten Chinese provinces and cities the “core” of Xi Jinping.

On February 10, the Beijing website Duowei published an article entitled “Core X. The path of China's new strong leader." When mentioning Jiang Zemin, it is noted that Jiang Zemin, who came to power after the Tiananmen massacre, can be considered a child of the regime. Thus, although Jiang had the support of powerful elders, the most he could be was a transitional figure, which was extremely difficult to call a “core.”

According to political commentator Shi Jiufen, the appearance of the term "Xi's core" certainly means the end of "Jiang's core" and may be a preparation by the authorities to settle scores with Jiang.

Specifics of economic reforms in China. Testaments of Deng and Jiang Zemin.

a) The content of the doctrine of “specific features of Chinese socialism.” The turning point in the history of modern China, which marked the beginning of profound transformations and restructuring of the country, was the Third Plenum of the Central Committee of the CPC of the 2nd convocation in December 1978. A fundamentally new strategy for economic transformation and modernization of the Chinese state was developed. Ideologically, the new strategy was developed in the form of the doctrine of building socialism with Chinese characteristics.” It should be noted that this concept was the main link of the entire reform policy. It meant a radical revision of orthodox Maoist ideas about socialism. At the same time, despite fundamentally different approaches to the implementation of the specific features of socialism, there is an amazing continuity of ideological positions. The idea of the specifics of Chinese socialism was laid down by Mao Zedong, but subsequently, each of the Chinese leaders sought to make their own specific contribution to the development of “Mao Zedong Sixiang” in order to become on a par with the classics of Marxism-Leninism.

Deng Xiaoping's course of radical reforms after Mao led to the formation of the theory of "the specificity of Chinese socialism." Basically, Chinese specifics, which ran like a red thread through all the congresses of the CPC, were each time supplemented with new provisions. The main meaning and content of this concept was that when building socialism, you need to follow your own path, and not copy someone else’s experience. This was one of the first conditions noted by Deng Xiaoping. The backwardness of the country, coupled with the presence of pre-capitalist relations in certain regions, also created special features of the transition to socialism. Deng Xiaoping is given credit for his transition to socialism in a country where capitalism was underdeveloped. No one could do this. The party charter, adopted at the beginning of the 21st century, included the provision that the “theory of Deng Xiaoping” about building “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is the guiding ideology of the CPC, that it is the “Marxism-Leninism of modern China.”

Based on the characteristics of Chinese development, Deng's theory shaped and detailed the concept of economic reform. Theorists of Chinese socialism after Mao Zedong built their policies taking into account the new historical period in which the country was located. The XIII Congress of the CPC, held in October 1987, paying attention to the creative, reformist side of Chinese politics, noted the peculiarities of the tasks in building socialism. At the same time, defining the role and place of the stage of historical development, the congress pointed to the initial stage of socialism in China. This meant that reforms in China were designed for the long term, that the country needed to develop everything that capitalism had not managed to develop.

The main features of Chinese socialism were defined by the congress as unshakable, not requiring proof, which in many ways resembled Maoism. The congress proceeded from the fact that it is necessary to firmly defend, not doubt or criticize the four main principles: the socialist path, the democratic dictatorship of the people, the leadership of the Communist Party of China, Marxism-Leninism and the thought of Mao Zedong. These principles served as the main basis on which the processes of economic reform and political struggle took place in the party.

It should be noted that the understanding of these principles by PRC politicians was viewed differently, just as different meanings were invested in them at each stage of the modern history of China. In the struggle for economic reforms, Deng Xiaoping put forward a number of criteria for the correctness of the course being pursued in China. To end the scholastic debate about which forms and methods of farming were socialist and which were not, Deng put forward three basic criteria for assessing the correctness of any policy. Their essence was that when solving economic and social problems one should think not about socialism and capitalism, but about the extent to which this policy contributes to the development of productive forces, the growth of the total power of the state and raising the living standards of the people. Dan did not go into detail about the specific features of socialism and capitalism; for him they simply did not exist. These three criteria became an important part of Deng Xiaoping's theory of "socialism with Chinese characteristics." The idea that one should not be afraid of capitalism, but that it is necessary to use not only its achievements, but also its principles, is one of the essential points in understanding Dan’s specifics of socialist construction.

Overcoming the socialist isolation of the Chinese state and the country's entry into the global market space led to a revision of the theoretical foundations of the party's economic policy. First of all, concepts and terminology changed, new slogans and mottos were put forward, but they reflected the main features of the initial stage of the development of socialism. During the Maoist period, planning and directiveness formed the basis of economic policy. The beginning of reform forced us to redefine the goals and specifics of the new policy. In China, the slogan of the “great march to the market” was announced. Theses arose that the party was implementing a “planned commodity economy” and creating a “socialist market economy,” but in the late 90s these interpretations were changed to the position of creating a “market economy” under socialism. Socialist utopian ideas were finally discarded and the path was cleared for the creation of democratic foundations in the field of economic development. The specifics of Chinese socialism moved further and further away from the tenets of previous Marxist and Maoist ideas about the features of socialist politics.

The specifics of socialism under Deng began to be reduced to the policy of implementing economic and social reforms, without all kinds of formational accents. In fact, the same position can be traced in the decisions of subsequent congresses of the CPC. After Deng Xiaoping, the new head of state, President Jiang Zemin, who also sought to become one of the classics of Chinese socialism, put forward his own theory, developing the concept of previous theorists, and above all Deng. According to tradition, every leader of the CPC must go down in history not only as a practical figure, but also as a theoretician and thinker. Therefore, new ideas had to be formally consolidated at the congress. In his report to the XV Congress, Jiang Zemin paid great attention to his ideas of “triple representation”, emphasizing the need for their further study and development in order to modernize the country. These ideas were strongly influenced and imitated by Deng Xiaoping. Jiang Zemin put forward three demands under which "the party can realize the main goals of reforming "socialism with a Chinese coloring." The three demands were that the CPC should represent, firstly, the advanced trends in the development of the productive forces, and secondly, the advanced achievements of science and culture, thirdly, the interests of the broad masses. The ideas are presented as a further development of Marxism-Leninism, the ideas of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. At the 16th Congress in 2002, these ideas were even proclaimed as the “Communist Manifesto of the 21st Century.” Jiang’s ambitions were satisfied , his ideas were canonized by the Party Congress and he was placed on a par with Marx, Lenin, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.

True, not all party members accepted the ideas of “triple representation” with enthusiasm. Many Chinese democrats called these ideas banal, hypocritical, aimed at preserving the one-party system. Some felt that these ideas were nothing new compared to Deng's three criteria. Few people in China could be confused by the congress's assertions that Jiang's ideas were the main stimulants for labor and the impetus for the modernization of the country. Material well-being, money and profit are what motivate people to work today and determine the activity of capital. The results of the 16th Congress were a significant success for Jiang Zemin, who approved the statement of the “threefold representation” in the new party charter. Be that as it may, the development of the main features and characteristics of Chinese socialism led far from the philosophy of class struggle and revolutionary violence instilled by Mao Zedong.

b) Features of transformations in agriculture. It is no coincidence that China began its transformation with reforms in agriculture. By the end of the 70s, 80% of the population lived in the Chinese countryside, most of them poor peasants. The reformers clearly understood that without reforms and growth in agriculture, no transformations in the economy and industry were possible. The Chinese village, completely ruined by Maoist bullying - the policy of the “Great Leap Forward” and the “Cultural Revolution”, was already ready for any reforms. Chinese leaders came up with the idea of restoring the past, age-old principles of peasants' interest in land labor. Land reform granted “from above” was not a new invention or insight of the Chinese leadership. The greatest merit of Deng Xiaoping and his supporters was that they were able to generalize and disseminate the creativity of the Chinese peasants themselves and the experience of the past throughout the country.

The reform actually began not with the formal decisions of the 1978 Sh Plenum, but, perhaps, with the mass protest of peasants and the peasant agreement in 1978 in the town of Fenyang, Anhui Province. The fact is that the hungry peasants, not wanting to endure hunger any longer, declared their complete disobedience to the authorities. This was not just a protest of people exhausted by poverty and constant lack. The peasants dissolved the commune and divided the land between households. Each peasant household took upon itself the obligation to hand over grain to the state and refused to seek financial assistance from the authorities. From the point of view of Chinese legislation, disobedience to authorities is a crime for which peasant leaders were punishable by death sentence. But no one disclosed the events in Anhui, and the authorities were able to observe the implementation of the reforms. Deng Xiaoping saw in the actions of his fellow countrymen a prototype of future land reforms. It can be considered that the “initiative of the people” was supported by the leaders of the Chinese government. The merit of reform leaders lies in their ability to direct the reform process in a controlled direction. In China, for the first time, “party regulations” were issued not against the opinion, but at the request of the peasant masses. This was the “democratism” of the reform and its success. The success of China's reforms began from the ground, with the liberalization of Chinese rural life and the rural economy.

In China, private ownership of land was not introduced, but peasants were given plots of land for use (on average 0.42 hectares per farm) and entered into long-term contracts for the supply of agricultural products. The entire harvest, in excess of the agreed volume, was placed at the disposal of commodity producers. After the “administrative revolution” of 1982, production brigades and communes were dissolved, and a massive transition of peasants to individual farming began. This was one of the most important initial stages in the development of village reform.

The peasant reform was called “contract responsibility for every peasant household.” The peasant family, and not the sole owner, became the manager of the land and its own harvest. However, it must be borne in mind that the peasants had the right to dispose of the products they grew, but they could not own and dispose of the land. In China, not only the sale, but also the sale of land was officially prohibited. In fact, it is a long-awaited tradition of the Chinese people. In the early 2000s, the system of family contracting for land quickly spread throughout the country. From now on, peasants had to give the state 20 percent of their production at fixed prices, and 20 percent to the cooperative for renting land. They could sell the rest of their products on the free market. The increased principles of material interest changed the attitude of peasants to work and gave a gigantic stimulus to the development of agriculture. The village began to transform before our eyes. The restoration of material interest and the liberation of personal initiative yielded results. A few years after the start of the Chinese reform, Deng Xiaoping officially announced the elimination of the problem of hunger in the country.

The reform became the basis and starting point of peasant prosperity. The peasants began to have real money, which they began to invest in the family business. Crafts and folk crafts began to revive and emerge. Savings were invested in production and commercial and industrial structures, called township village enterprises in China. At the same time, the reform freed a significant part of the peasant population, who were unable to farm in a market economy, or who could not withstand the new economic rhythm. Free workers appeared in the village. The authors of many articles argue about future problems associated with the growth of mass unemployment in rural areas, where the majority of China's population lives today.

The freed up workers were used in rural settlement enterprises, which were based on the principle of private entrepreneurship. They laid the foundation for a unique local rural industry. The first village enterprises appeared in the mid-80s and began with the production of processed agricultural products. Over the two decades of their existence, large associations such as export concerns of agricultural products have appeared. Tens of millions of Chinese peasants were involved in non-agricultural production in the countryside. They produced bricks, carried out repair work, and created sewing workshops. The production of cement, building materials and metal structures, plastic and wood products, dishes, shoes, clothing, all types of canned food, dried fruits began to be included in the list of production of local industrial enterprises in the village. About half of the township enterprises had imported equipment, and most goods were exported outside the provinces and abroad.

The growth rate of rural industry in the 90s developed within the range of 21-134%. This contributed to the saturation of goods and the satisfaction of consumer demand both in the countryside and in the city. To streamline many commercial processes, the law “On volost and settlement enterprises” was adopted in 1997. He established some rules for the relationship between village enterprises and the state and their rights. By the beginning of the century, private family cooperatives provided jobs for about 150 million people, producing 75% of China's rural gross domestic product. By the mid-90s, the state allowed village enterprises to engage in foreign economic activity. In 2000, more than 150 thousand village enterprises worked for export in China. Large enterprises were gradually formed with the participation of the state and foreign capital, mainly foreign Chinese - huaqiao.

Party and state leaders closely monitored the ongoing processes in the countryside and tried to exercise fairly strong control. They were concerned, first of all, about the possibility of mass landlessness among peasants and the exodus of hundreds of millions of unemployed people to the cities. State and party bodies controlled the ownership of land plots and exercised control over the products produced. The state controlled the prices of basic agricultural products, primarily rice and cotton. Chinese leaders were aware that, despite the control and restrictions in the village, there was still unofficial sublease of land, transfer of land plots on collateral. Without the participation of the authorities, illegal land circulation existed. The need for further land reform is already ripe, but China's leaders after Deng Xiaoping are in no hurry to do this, realizing the possibility of new, more complex problems arising related to the gigantic population, which already exceeds 1.2 billion inhabitants, and by the middle of the new century the number of Chinese will increase by 1.5 billion people.

The successes of Chinese reforms were significant during the period of liquidation of the consequences of Maoist socialism. However, by the end of the 90s, the economic resource founded by Deng Xiaoping had already exhausted itself. The reforms required their further development, a new stage of transformation. A lot of time has passed since the time of Deng Xiaoping, which has accumulated new, more complex problems, the solution of which also required the efforts of large-scale reforms necessary to solve problems within the framework of the processes of commercialization of public life. The need to improve the family contract system, as well as village taxation, reform the structure of counties and volosts, and organize villages at the grassroots level became obvious. This was already the problem of the “fourth generation” of Chinese reformers. At the beginning of the new century, CCP leaders announced the need to change forms of land ownership. Peasants cultivating the land were given the opportunity to buy and sell plots of land. All this indicated that the Chinese leadership understood the need to resolve pressing reform issues after Deng. A change of generations of government officials took place at the 16th CPC Congress in 2002. The new leaders of Chinese power in the new century will have to solve economic problems and, above all, problems in agriculture.

China is on the verge of a new round of economic reforms, on which the stability of the Chinese state depends. One of the main problems that required immediate resolution was unemployment, which in 2004 amounted to about 150 million people. Agrarian reforms caused an increase in surplus labor in the countryside. Urban industry, despite its growth, as well as the development of volost settlement enterprises, was unable to absorb such a massive influx of new workers. The country was not ready for the process of urbanization of the country.

The success of Chinese reforms in agriculture is undeniable. Their results speak about this. The global statistics are truly impressive. China, which owns 7% of the world's arable land, successfully provides, taking into account the Chinese population, 22% of the world's population. A record grain harvest of 465 million tons was harvested in 1995, and with the lowest post-harvest losses, China began to lead the world in grain production. The harvest in 2001 amounted to 460 million tons, in 2002 - 452 million tons. Since the late 90s, a certain stagnation in agricultural production has begun to be observed. This suggests that the reform opportunities laid down by Deng Xiaoping have already been exhausted. A new step forward along the path of transformation is needed. It is no coincidence that the 16th Congress of the CPC emphasized the need to change the forms of land ownership. This means that the chosen course of reforms will be continued.

And yet, for China, the problem of providing the country with grain remains a global agricultural task in the 21st century. Despite the world's highest gross grain yield and low product losses, China lags behind other grain producers in terms of yield per hectare of land. This was the main reason why China, producing gigantic volumes of agricultural products, was forced to import grain and by the beginning of the new century had become the largest importer of grain. And China itself, judging by the statements of Chinese leaders, considers itself a developing country and is trying to convince the whole world of this. This is not far from the truth.

c) Specifics of modernization and reforms in industry. How can we not remember here that the basic industries of China were created by the Soviet Union in the 50s and 60s on the basis of “brotherly assistance” to the great Chinese people. During these years, Chinese industry was created on the basis of the technical achievements of the USSR, its financial and economic assistance. Thousands of factories and enterprises were built in China, constituting the basic industries of China. Chinese industry was completely focused on Soviet raw materials and technical support; exact copies of Soviet cars, machine tools, aircraft and tanks were produced. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Soviet Union took part in forming the foundations for the future modernization of the country. Economic assistance did not disappear without a trace; it nevertheless created the foundations for the industrialization of the country at the first stage of the formation of the Chinese economy. And although the former “big brother” now has a lot to learn from the Chinese, it should be noted that the new stage of economic and technological success and the modernization stage of Deng Xiaoping has been completed thanks to the reform and transformation of China's core industries.

After Maoist experiments in large-scale industrialization in the late 70s, the problem arose of choosing a development model for China, which was supposed to determine the path of the Chinese economy as a whole and determine further social development. In China's conditions, the choice of a model for creating a self-sufficient closed-type industrial economy, which is focused on the needs and opportunities of the domestic market, was quite realistic. This model significantly limited the processes of China's participation in the globalization of the modern world. The second model was based on the idea of structural and technological transformations in the basic sectors of the economy, which assumed full participation in the international division of labor and the world economic economy. This model assumed the integration of the country into various spheres of the international economy.

Deng Xiaoping's reforms were initially focused on broad participation in the global economic space and on the export specialization of industry. Structural restructuring of the national economy, its basic foundations, has demonstrated its effectiveness and shown its advantages not only in China, but also in many countries in Southeast Asia. China has purposefully begun to modernize outdated production facilities and replace them with the latest technologies in the world. In 1981, plans included an increase in production based on new economic relations. The birth of the idea of the possibility of market relations under socialism served as the beginning of transformations in industry. The government's main concern was the priority development of knowledge-intensive industries for export production.

Since the beginning of the 80s, restrictions on state planning and centralization of the economy began to be implemented. Industry was gradually freed from all kinds of administrative fetters on the basis of the liberalization of commodity-money relations in the economy. Enterprises, having received freedom from all kinds of approvals, began to sell most of their products on the market. Wages were set depending on the profit received. The state moved to encourage private enterprise and allowed the use of hired labor. The activities of mixed enterprises are allowed. Gradually, the share of various economic sectors in China has changed. If in the early 70s, 96% of the entire economy was made up of the public sector, then by the mid-90s its share was reduced to 40 percent. The role and importance of the private sector increased. Subsequently, the share of state-owned enterprises in industrial production continued to decline, falling to 24 percent in 2004.

Deng Xiaoping used the ideas of socialism in his reforms, understanding their significance for the majority of the Chinese people. In the practice of reform, he was forced to avoid destructive measures for the public sector in the economic sphere. The public sector was not affected by privatization and radical reform. Based on socialism, Deng reformed it into its complete opposite. Deng's successor and follower, Jiang Zemin, resorted less and less to socialist terminology and rhetoric at congresses. At the 16th CPC Congress in 2002, the Chinese leader noted that state-owned enterprises remain the main pillar of the national economy, but they will compete with private enterprises on equal terms. In fact, this meant abandoning the strategy of the decisive role of the public sector in the country's economy. Jiang Zemin demanded that laws ensure the development of the non-state sector of the economy and protect the rights of private owners. The ideas of the “triple representation” of the departed General Secretary Jiang were no longer filled with the ideologies of the previous formation, but were built on pragmatism and a new understanding of the methods of creating a new society.

A distinctive feature of the reforms carried out in China is their duration and phased nature. The reasons for such a cautious and gradual approach were explained, first of all, by the possible consequences of a political and socio-economic nature in the context of the country’s huge human resource. Reforms in agriculture and industry could not but entail a reduction in the number of employees without guaranteeing their employment. This process could have serious consequences for China. On the other hand, the party bureaucracy feared the loss of its control over the economic sphere. Therefore, even if greater freedoms were granted to industrial enterprises in the public sector, it was while maintaining the strict framework of party and administrative directives. Thus, the “Law on Industrial Enterprises of National Property” of 1988 confirmed that the primary organization at the enterprise exercises and guarantees control over the consistent implementation of the policies of the party and the state. Deng's policies required priority treatment of state-owned enterprises.

However, all the attempts made by the leaders of the PRC after Deng, aimed at reviving the commercial activities of economic state structures, did not achieve the desired results. One of Jiang Zemin's attempts to carry out industrial reform in 1995 ended in failure. With the loss of economic positions, it became increasingly difficult for the public sector to play the role of a social stabilizer. Therefore, the political struggle in China increasingly became part of the solution to the main question of the 21st century: where and in what ways will China go next? What reforms await the Chinese after Deng Xiaoping?

The most important specificity of industrial reform is the absence of privatization, in its Russian understanding. Deng Xiaoping did not encroach on the foundations of state ownership, maintaining the “socialist” base. Reformers in China studiously avoided the term “privatization.” Privatization in the PRC was declared a negative phenomenon, but the right to collective and joint-stock forms of ownership was recognized. It's not just a matter of terminological uncertainty. The transition to a market required the implementation of measures characteristic of market laws. The development of industry under Deng did not proceed through the reform of state property and its privatization, but through an increase in the number of mixed and private forms. Subsequent reformers, led by Jiang Zemin, were forced, subject to market laws, to move on to liquidating ineffective state-owned enterprises.

In 1997, the country's leadership once again announced industrial reform. It was announced about the upcoming corporatization of ineffective enterprises and the creation of commercial structures on their basis. The main areas of their activity should be telecommunications, electronics and petrochemicals. That is, since the late 90s, the process of denationalization of property began. This process was very slow and became the object of political struggle. The next campaign to corporatize state property dates back to 2000, when the program for reforming state-owned enterprises was promulgated. It was planned to reduce the share of the public sector in the country's economy by 2010, leaving transport, communications, metallurgy and chemistry under state control. Deng Xiaoping, when starting reforms, did not encroach on the main positions of the public sector; the reformer's followers were forced to continue the reforms, without which reforms towards the development of market principles of economics are impossible. This did not at all mean a rejection of the principles of Deng Xiaoping. Deng's main behest, which former and current reformers strictly follow, is that all reforms are acceptable if they contribute to economic development and strengthening of the state. This also corresponds to the legacy of Confucius, who argued that “what is good for China is good for everyone.” Thus, at the beginning of the third millennium, China once again found itself on the threshold of a new stage of significant change.

During the course of economic reforms, China changed its appearance; it became different, both in the economic and social spheres. The role of party officials - gan-bu - was changing. They became not only organizers, but also participants in the market economy. Doctor of Historical Sciences L. Delyusin in one of his works drew attention to the fact that the backbone of the party began to engage in commercial activities. The party has become a commercial-democratic organization, at the center of which is party-state ownership. Therefore, the Ganbu actively advocated “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” which created conditions for the development of market relations and at the same time consolidated the administrative-command management system. This was the basis for the main reforms of Deng, who was unable to completely encroach on the structures that formed the basis of Chinese socialism. Rather, Deng took into account the possibility of unstable development in the event of more radical steps by the Chinese leadership in making the transition to a market method of economic management.

Deng needed to rely on the social strata that actually existed in post-Mao society. He carried out his reforms, relying on workers from the ra-, peasants and the intelligentsia, equated to the slave-peasant stratum. But time passed, reforms developed, new propertied social groups appeared in the region. The followers of the reform radically changed the social support during the construction of Chinese socialism. Jiang Zemin, having taken over the management of the country after Deng, sought his social support in the emerging class of owners.

The processes of restructuring in society were accompanied by a political struggle with competitors in the struggle for power and the pursued political course. President Jiang, like Deng in his time, managed to consolidate power and occupy the most important political positions in the state. He simultaneously held the posts of “zhuxi” (president), general secretary of the CPC Central Committee, and concentrated on himself the most important levers of army control. Having retained a monopoly on power, he, like Deng, carried out a large-scale reorganization of the state economy and decided to actually privatize unprofitable enterprises. Over the years of his activity, he began to be called the “chief engineer of reforms.” Jiang acted as the “faithful successor” of Deng, whom Chinese propaganda called the “chief architect” of reforms. A new “cult of Jiang” was formed. Jiang surpassed Deng Xiaoping in real power and actually became equal to the “great helmsman” Mao Zedong. It is no coincidence that the 16th Congress in 2002, summing up the activities of Jiang Zemin, noted that the course of the “chief engineer” of Jiang’s reforms not only does not contradict Marxism-Leninism, Mao and Deng, but is almost the only possible continuation of it.

Openness of the economy (kaifang) is one of the characteristic features of the reform, the foundations of which were laid by Deng Xiaoping. Deng's call to “not be afraid of the West” was further developed in China. But even Deng avoided rapid liberalization in the foreign economic activities of the Chinese state. He feared, first of all, possible troubles associated with the lack of competition of Chinese goods and the increasing influence of foreign states. Deng's followers continued their foreign economic policy towards economic rapprochement with other states. Having joined the WTO in November 2001, China immediately stepped up economic rapprochement with East Asian countries, most notably Japan and Korea. Relations with Russia have become more open and trusting. Jiang Zemin knew and loved Russia and its culture. He had a passable command of the Russian language (he had an internship at the ZIS automobile plant), and could sing “Moscow Nights” or “Let’s Sing, Friends.” At a meeting with the first President of Russia Boris Yeltsin in 1998, he reminded those present of these Russian melodies and songs.

In terms of industrial production growth, which was growing at an annual rate of 11 percent, and in terms of gross indicators of many types of production, China entered the top ten countries in the world. The PRC's share of world GDP in 2000 was already almost one and a half times greater than that of Japan. However, economic growth by the end of the 90s, which coincided with the end of Jiang Zemin's leadership of the country, slowed down somewhat. This suggests that the peak of production growth based on reform has already been passed. The main indicators indicate that the quantitative growth of industry, as well as Deng’s reforms, have exhausted themselves. Jiang Zemin, having become a true successor to the legacy of the great reformer, made significant progress along the path of the Deng reformation, but with the beginning of the new century this was not enough. A structural restructuring of the entire industry is needed. In addition, new steps are needed in the transition from a centralized economy with market relations to a higher quality of relations corresponding to a new stage in the 21st century. This was to be done by the new generation of Chinese leaders.

d) Traditions and reforms in modern China. The “specificity of Chinese socialism” lies in the fact that it is built on the traditions of the Chinese way of life, on ideas and morals familiar to every Chinese, rooted in ancient times. The worldview of the Chinese people and their traditions are connected not only by the ideas of Confucian morality and order in society. Other religious worldviews have also been preserved in China. They are united by common, despite their differences, philosophical principles of life, which can well be argued about a unified ideological system of Chinese civilization, starting from the time of Confucius. Many of these traditions formed the basis for the transformations of modern times. All transformations carried out “from above” were based on the traditional worldview of the Chinese population and bore the imprint of the traditional culture of China, the main principle of which is based on the primacy of state interests over personal ones.

Mao Zedong, starting the “great proletarian cultural revolution,” was unable to get rid of old traditions and customs, ideas and forms of governing society. The “Red Guards,” destroying the remnants of the “bad old times,” revived old traditions in a new guise. While fighting the Middle Ages, Mao involuntarily returned to it, to its principles, foundations and ideas. Declaring a fight against Confucius, Mao himself tried to become one. In fact, Mao’s quotation books became the bible for the Red Guards and their supporters, those who carried out the “cultural revolution.” Mao Zedong's greatness was akin to that of the Chinese emperor, and some paid him almost divine honors. Many authors have noted that Confucius defeated Mao. Confucius returned to Chinese society, and the “little little books,” like Mao himself, gradually became part of the past.

The new Marxist-Leninists, having taken the helm of the Chinese state after Mao Zedong, found it necessary and useful to use traditional consciousness in new endeavors of a liberal political course. All reforms, whatever they may be, are based on the ideas of traditional nationalism, the most ancient views that have been supported for centuries in China - loyalty to the nation and gratitude for the opportunity to be born Chinese, loyalty to the family and respect for elders. Another ancient tendency that has acquired a new meaning in the social life of the Chinese - the interpretation of the struggle between public order and personal enrichment - received clear expression twenty-five centuries ago. Deng Xiaoping, putting forward the motto of his reforms, “Being rich is also not bad,” relied on the foundations of Confucian morality.

From the Confucian heritage, Deng Xiaoping took the concept of “xiaokang”, meaning “small prosperity”, to define the goals of economic development. In Chinese history, it was traditionally believed that the xiaokang period preceded the creation of the Da Tong society, a society of universal unity and harmony, when “the Celestial Empire belonged to everyone.” Xiaokang came to be regarded as a level of average prosperity, which was defined differently in different regions of China. Jiang Zemin, continuing to develop the general Confucian approach, stated that by the middle of this century it is necessary to significantly increase the level of material well-being of the Chinese, to move from improving the lives of social classes to improving the lives of the entire people. The decisions of the 16th Congress of the CPC in 2002 declared the continuation of the chosen course, that the party would contribute to the comprehensive construction of a “moderately prosperous society” (xiaokang). At the same time, Jiang drew attention to the need to use all the human resources of the country, primarily the intelligentsia and entrepreneurs. The followers of the Reformation radically changed the social support when building Chinese socialism.

The ideas of Confucius were adopted by the Chinese government to legitimize ongoing market reforms. Confucian attitudes and worldview fit much more comfortably on Chinese soil than communist ideas. Everything that determined the essence of Deng Xiaoping’s land reforms was built on the basis of traditional peasant consciousness about land and property. Land in the country has historically been viewed primarily as a state (public) property. In the “family contract”, which underlies land reform, there is a tendency to preserve traditional forms of management on Chinese soil. This explains the apparent half-heartedness or incompleteness of the reform. The land was not transferred to private ownership, but was given to the “contract responsibility of the peasant household.” For the most part, the Chinese peasant acted as a tenant, but not as an owner of the land. This has always been the case in China.

It is noteworthy that Deng Xiaoping’s reformers did not try to eliminate the family-clan relations that had long been established in industrial relations. The principle of family-clan ties, introduced into the sphere of land relations and commerce, becomes dominant in the sphere of business structures. A. Fedorovsky emphasized that even if large corporations arise, they are still managed in accordance with the principles of family hierarchy. Much of the tradition of family-clan structures proved useful in carrying out economic transformations. The priority of discipline, a strict system of seniority, and devotion to the employer proclaimed by Confucianism in the patriarchal peasant family replaced the need for “party educational work,” which, by the way, was built on the same foundations.

Reformers tried to preserve the peasantry as a special social group of the Chinese population. Krest-Kt>V° constituted and constitutes the majority of the population - 800 million. Until the beginning of the new century in

China has had a “resident population registration system” since 1955. The peasantry found itself isolated from the urban population and, according to the law, was attached to the land, a permanent place of residence. Village residents were assigned responsibilities to work on the land, provide the city with food, and industry with raw materials. Limiting the initiative of the population and consolidating economic inequality preserved the backwardness of the village and assigned medieval features to it. For peasants, the possibilities of changing rural to urban registration were very limited, unless they received a referral after a university or made a career within the framework of the system of personnel workers - ganbu. In many ways, this was reminiscent of the peculiar system of serfdom that survived under Chinese socialism until the beginning of the 21st century.

The consolidation of the peasantry as a social stratum with its patriarchal order made it possible for the state not to participate in the organization of social protection, leaving them to solve many problems themselves. This was a policy aimed at ensuring that the majority of the population provided food for itself. In addition, registration served as a barrier holding back the influx of peasants into the cities. In 2000, up to 100 million people were concentrated in the countryside, with labor surplus for agriculture. At the same time, the isolation of the peasantry created a lot of problems. The registration system increased social inequality. Citizens were guaranteed a higher standard of living through social security and benefits. The government, exercising control over pricing, subsidized citizens through guaranteed prices for food products. The urban population has become a privileged social class.

Under Deng, in 1984, some relief was made for peasants to travel to the cities, but without the right to register as city residents. After the events in Tiananmen Square in 1989, a large part of the villagers were sent back to the villages. By the end of the 90s, the negative consequences of the registration system worsened. In 1992, peasants were given the opportunity to buy city registration. Only wealthy peasants could become townspeople. Only in 2002 was rural registration abolished and a unified registration system for Chinese citizens was introduced. Jiang Zemin began experiments to change this order and put an end to the medieval tradition, which had completely become obsolete under the conditions of the new political course.

Thus, a feature of the Chinese path to socialism is its respect for national traditions and spiritual heritage. China's new leaders have no intention of breaking their ties with ancient thinkers. In conditions when the country is overtaken by crisis phenomena, references to the great Chinese “Book of Changes”, which says that, having reached the limit of its prosperity, the Celestial Empire must again enter a period of temporary disasters, are the best place. But the new rulers of the PRC, taking into account the dialectical cyclical nature of China’s development, are not going to experience a period of crisis and are making attempts at further reforms and transformations in order to ensure the progressive development of the Chinese economy.